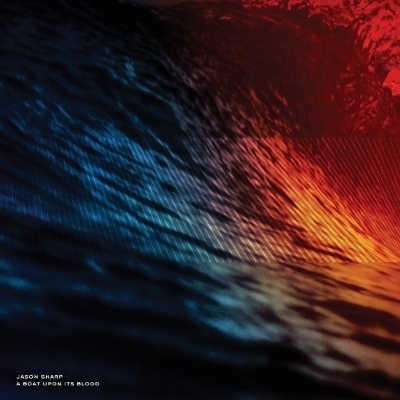

Baritone and bass saxophonist Jason Sharp is a long-time collaborator with poet Kaie Kellough and has been involved in the Montreal music scene for several years as a member of large ensembles (Sam Shalabi’s Land of Kush, and Nicolas Caloia’s Ratchet Orchestra), playing with Matana Roberts and Thee Silver Mt. Zion Orchestra, and opening for visiting free-jazz giants like Peter Brötzmann and David S. Ware. A Boat Upon Its Blood, Sharp’s debut disc, speaks obliquely to this varied background; its stylistic catholicism, drawing freely from, for instance, electroacoustic, free jazz, film-score, and techno tropes, never gives way to pastiche or virtuosity. Organized into two suites and a two-part interlude, the music on the album ebbs and flows with equally organic and electronic textures, and occasionally erupts into noisy climaxes in a tightly composed, almost cinematic scheme.

Inspired by a Robert Creeley poem, the first three-part suite, A Boat Upon Its Blood, begins with atmospheric minor-key drones, hums, whistles, and pulses. The second part of the suite introduces slightly more abrasive timbres and discordant harmonies, but stays true to the flowing structure; and a subtle pulsing ostinato in the deep bass grounds the piece. The triptych concludes with a quasi-techno beat built on relentless percussion, glacial bass, and eerie synth semitones, which anchors whistling and bubbling electronics and builds to an anxious climax before abruptly giving way to silence. Far from any recognizable jazz or new music, the piece’s evocative fluidity and ambiguous intensity bring to mind Carmine Coppola’s soundtrack for Apocalypse Now, filtered through the new school of electronic music exemplified by Tim Hecker and Ben Frost. Fundamentally, it is narrative music; it subsumes a wide variety of techniques from disparate genres, not into the moulds of song or improvisation but into something more like the classical modes of the suite or tone poem, circling around and honing in on a particular intensity.

The two-part interlude separates the album’s minimalist and maximalist impulses. “In The Construction Of The Chest, There Is A Heart” sets high whistling tones (processed horns?) against an increasingly insistent pulse that morphs into shuffling percussion, while the second part of the interlude, “A Blast At Best,” is the closest thing to free jazz on the album. Coming off as a twenty-first-century take on the Jazz Composers’ Orchestra’s Preview (featured in Joyce Weiland’s Rat Life and Diet in North America), guttural and screaming saxes play off each other against another tense backdrop of . . . what? The distinction between acoustic and electronic instrumentation seems to dissolve throughout the album into an organic continuity of synths and processed horns, strings, and drums.

The album ends with another suite, the two-part Still I Sit, With You Inside Me. Melancholy strings predominate in the piece’s first part, backed by hollow howls, drones, and industrial revs. The concluding half introduces a pretty Michael Nyman-esque guitar and violin dialogue, given a hint of menace by the barely detectable entry of a bass, followed by high tremolo from the strings. Eventually the bass drowns out the strings and the piece gives way to another uneasy pulsing soundscape, building to a noisy free-for-all before, again, giving way to echo and then silence.