IT’S 2016, YET I FIND MYSELF SPENDING an inordinate amount of time talking about artistic output from the ’70s and ’80s. It was in the latter decade that esteemed Montreal-based sound poet Kaie Kellough’s favourite band, Bad Brains, emerged on the scene with a self-titled debut that advanced the “hard” in hardcore punk. If you need a one-way ticket “black to the future,” Kellough has no issue helping you book it: “I’ve always been attracted to people who play instruments or use words to expand the boundaries of music and thought—anyone from Caribbean poet Kamau Brathwaite and [American poet] Jayne Cortez to the bebop vanguard: Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.”

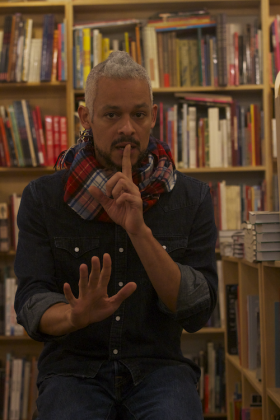

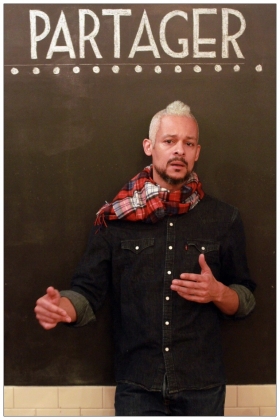

Engaging Kellough in conversation involves moving through multiple layers of historical Afro-diasporic artistic access points. A writer, poet, and word-sound systemizer (as he refers to himself on his Twitter homepage), his conversation is speckled with silences that are every bit as expressive as the words he uses to illuminate his artistic practice. I know as much about what a word-sound systemizer is as the next person, which is probably not that much; and perhaps that’s the point. “Whether you call me a poet, sound poet, word-sound systemizer . . . it all doesn’t matter. I am a writer first and foremost, because everything begins with language. I also work in sound creation and use visuals. But language is where it’s at. Language is emotional. Language is visual. Language is visceral. There’s a certain level of sustained inquiry and engagement we can all find in language.”

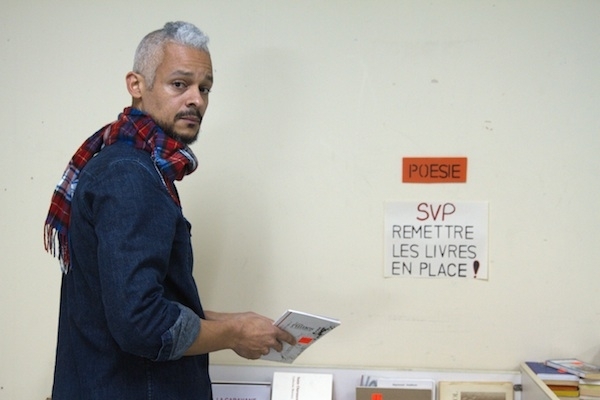

A prolific working sound poet, Kellough has plied his craft across Canada and internationally, working solo, with live instrumental accompaniment, and with large musical ensembles; over a four-year period in the mid-2000s he gave over 300 performances. His second published book of poetry,

Maple Leaf Rag (Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2010)—named after Scott Joplin’s renowned ragtime tune, and experimenting with different types of writing—further catapulted him into the public consciousness. Just as he takes his words from the page to the stage, there is an element of performance in his conversation, too—whether intentional or not. The productive performance poet must have the ability to engage listeners (including interviewers),

and so, many of Kellough’s words are articulated with a very specific intent, and his verses threaded together for effect. Given his diverse literary, audio, and video output, it’s no surprise he seems to jump through, between, around, and over artistic mediums in a single bound.

Whether riffing about the dub innovations of Augustus Pablo that influence his work or about his fondness for plants (“they carry out their silent life and are amazing things, if you are a musician, because you have to listen to your plants in a way that’s not exactly the same way you listen to sound,” he says), Kellough’s verbal prose brings to mind a theory of language called “the speech act.” John L. Austin coined this term—which can be found in his seminal book How to Do Things with Words (Clarendon Press, 1962)—to describe the way the voice does things with words as a mode of action rather than just simply conveying information. And Kellough just might be a speech actor of the highest form. Kellough’s written, verbal, and audio output takes apart language, words, music, and then suplex-slams them on their heads, while keeping things relatively rhythmic and melodic on a case-by-case basis. Much like the alliteration found in his name and that of his favourite punk band, literary devices and word manipulations figure prominently in his performances.

After taking in a live performance of his bebop-inflected “AlphabetA”—a re-articulation of the alphabetic sequence, going from A to Z, and Z back to A, with pauses at different moments to riff on and expose the sounds of the letters—you might need to go take a cold shower or inhale a few pints of lager. His wholesale decapitation and deconstruction of the alphabet is scintillating. “There is a structure at play there, but there is also plenty of room for improvisation,” he says of performing the piece. “Early on, when I would rehearse that piece, it would produce a kind of euphoria. That piece is a bit of a high-wire act. It happens quite fast, and it has to happen with precision.”

Still others (like me) might argue that the pièce de résistance across his broad body of multidisciplinary work is Distress Signal, his “voideo” (where voice meets video) that employs the use of a Photo Theremin, a Morse Code phone app, and an iPhone LED light. At a time when the plight of displaced Syrian refugees has captured the imaginations of people across continents, Kellough’s prescient piece of sound art (recorded in 2014 and performed live with bass saxophonist Jason Sharp, his frequent collaborator, at the launch of his record Creole Continuum) indirectly speaks to the feelings of displacement felt by many refugees who struggle with notions of home. It also speaks to those who refer to themselves as hyphenated Canadians—people like myself, born in Canada but with roots from elsewhere, whose parents might have come to Canada for a better life, but who sometimes feel torn between two worlds. It’s an intensely urgent, life-altering piece of postapocalyptic video and performance art with low production values but high synapse-firing of potential that mere words in print cannot do justice to. The video screen reads: “this is a distress signal . . . we were abducted . . . we want to return . . . we do not know where home may be.” Distress Signal is open to multiple interpretations and could be referring to anything, from the alien E.T. (extra terrestrial) in Steven Spielberg’s film of the same name, to the millions of Africans forcibly removed from their original homeland as part of the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

When asked what exactly this video-art piece means, Kellough is cagey at first. “It’s an enigmatic little entity that is not a song; it’s not a commercial; it’s something floating out there in cyberspace.” But when pressed further, he lets the alien out of the spacecraft. “Maybe it’s a cosmic message in a bottle … or can speak to feelings of displacement, or people trapped in an unfortunate situation, maybe a relationship that they can’t escape from.”

BORN IN 1975 IN VANCOUVER but raised mostly in Calgary, Kellough began his dynamic literary crawl through Canadian life around the same time that Sony released the Betamax videotape—a format that became largely obsolete because rival electronics giant JVC developed a more widely accessible format. Rather than fight an uphill battle, Sony conceded defeat and let Betamax wither into irrelevance (production will finally cease in March 2016). Growing up in Calgary, Kellough must have felt like Sony, fighting a losing uphill battle as a racialized child growing up in a homogenous environment that felt nothing like today’s more progressive city, which is led by Mayor Naheed Nenshi, the first racialized Muslim mayor of a large Canadian city.

“One of the reasons that I wanted to start writing is that I felt that something in me was ready to bust,” Kellough says in plain terms about the racism he felt. “Growing up in Calgary in the ’80s, when Preston Manning’s Reform Party was in its ascendancy, was not a nice time to be there … you almost felt despised. There was a really aggressive conservative culture: a lot of racism and exclusion. Writing offered me somewhat of a vocabulary and outlet to discuss those experiences. I turned to writing to make sense of the world around me.”

Reading poetry by African-American authors attached to the Harlem Renaissance, and seeing how the writers articulated their experiences with racism made Kellough feel he could use the literary medium to disseminate some ideas about his own cultural experiences. “I remember reading this stuff and thinking, Holy shit! I had never read anything like this. My mind was blown. You could actually talk about this stuff [race], in this medium, in this way? When you are seventeen or eighteen years old, trying to align how you feel and your relationship with the world, what you experience on public transit, reading these works changes you.”

Hell-bent on fleeing the general drabness of Calgary cultural life, Kellough left for Montreal in 1998 to, as he says, “launch myself as far away as possible from Calgary in a single bound.” The emotional scars have still not fully healed. “As a forty-year-old man, I still carry those embittering experiences that I still associate with Calgary, even though I’m no longer experiencing them in the moment.”

MONTREAL, WHERE KELLOUGH STILL RESIDES, not only ended up being a city of refuge for his multiculti polyglot ways, it also just happened to be the city where his parents met (his father is Vancouver-born and Saskatchewan bred with Irish-Canadian roots, and his mother is Guyanese). Relocating to a city with a cultural makeup more varied than Calgary’s, to a place with deep historical and political tensions, intrigued him. “Being born in 1975 meant coming of age during the time when the idea of Quebec was very important to the idea of Canada and the Canadian imagination. It was a hotbed of political and social activity, whether you were hearing about the October Crisis, questions around national unity, or incredibly polarizing figures like René Lévesque. I came here to investigate that.”

Montreal played a prominent role in his 2015 short-fiction collection Navette (“shuttle” in English), which tells the story of a young man of Haitian descent growing up in Montreal. “The idea of wrestling with the tensions found here is very important to a writer,” says the bilingual Kellough. “The idea of language being thought of as something that is not just communicated publicly—that is as necessary to one’s survival as air or water, something that was fought over—is profound.”

After having lived in Montreal for the last seventeen years, Kellough still excitably revels in what the city offers his soul. He cites Toronto-based dub poet Clifton Joseph’s notion of an “immigrant groove” as one of the things that keeps him in the city and stimulates him, enthusing about how wonderful it is to live in a part of town that is so close to Petit Maghreb, the first neighbourhood in North America to be heavily populated by North African merchants, set within close proximity to areas with sizable Haitian, Latin American, Italian, and Québécois communities. Whereas some Canadians of immigrant stock might desire to shed their ethnocultural origins, leave their ethnic enclaves for the sake of full-on assimilation, or fully embrace the Canadian Holy Trinity—hockey, beer, and rock ’n’ roll—Kellough takes the opposite approach. “I see some people have that desire or dream to blend into Canada and become 100 per cent Canadian, whatever that means. Despite being born here, I have zero interest whatsoever in that. I come from a family that’s partly from somewhere else, so this multicultural mix in Montreal feels more familiar and comforting to me.”

For many racialized, hyphenated Canadian artists, the push and pull of the non-Canadian half of one’s identity sometimes means that many waking hours are spent reconciling one’s immigrant histories. This tug of war is what informed his 2014 record Creole Continuum, its title drawn from 1960s studies in linguistics in societies in which a Creole is established. Much in the way that many cultures examine their relationship to language and power, based on an attachment to a dominant culture’s language, Kellough’s record sonically “identifies degrees of mixing between the Creole and the dominant tongue.” For Kellough that could mean juxtaposing the Guyanese Nation Language, heard on his mother’s side of the family, to the Queen’s English. Guyana had always figured prominently in his life, starting as a backdrop, then moving closer to the foreground of his life and artistic practice as he got older. “The Guyanese side of my family, who are all in Vancouver, had a very strong influence on me, growing up. I’ve always had this awareness of this parallel universe, an awareness of another place that you belonged to.”

The form of music that Kellough returns to most often—and the one that informs his own music practice—is Jamaican roots reggae of the 1970s. The way that very limited audio resources were used to reach back to reggae’s musical roots and to recontextualize all kinds of wildly interesting sounds—including found ones—serves as an inspirational tool for his own music productions. “Jamaican roots reggae is some of the richest and the most expansive music in the world, because it’s a music that carries in it a historic memory that sonically stretches back to Africa. It carries with it so much of the sonic properties of the natural world.”

WHILE DEVELOPING HIS MOST RECENT project, Essequibo Sound System, Kellough aimed to prioritize the sounds and voices of Guyana, much like the Jamaican sound system inspirations that came before him. “When I was in Guyana, my brother and I were listening to frogs nearby the rainforest and we weren’t sure if they were bullfrogs or not, but they were making this incredible sound (he mimics the burping sound over the phone). And then I thought to myself that I know that sound: that’s the sound of a guitar and keyboard skank in reggae music.”

Channelling his inner Lee “Scratch” Perry, Kellough is storing in two suitcases much of the electronic gear he’s been collecting over the years, and a small modular synthesizer that he’s been building over the last little while, and intends to travel to Guyana’s capital city, Georgetown, in 2016 to record “the sounds of Guyana,” and incorporate those sounds into the Essequibo Sound System. And 2016 just happens to be Guyana’s fiftieth anniversary of independence, so Kellough’s latest brainchild will serve as his audio love letter to his mother’s birthplace.

“Georgetown is interesting because it’s a small city, but extremely loud and cacophonous. It’s got a real pulse and jangled cacophony and bustle that you find in larger cities. It’s intense and, sonically, an extremely rich place. There’s the meeting of the rainforest and the natural sounds with all of the urban sounds.”

He wouldn't be the word-sound systemizer that he is if he wasn’t plotting some way to populate his own wordplay with the sounds of Guyana’s sonic habitat. “The idea is to use the sounds of nature and the urban sounds that exist in Georgetown as a compositional tool and to create works based on that overlapping of sounds. And this could mean adding vocal articulations, talking, screaming, mumbling, whatever. To have language as a presence in there.”

Though still quite young as a practising poet, Kellough is already thinking about his own legacy and creating works not just to be enjoyed for today but for posterity. “Broadly speaking, I am trying to put something into the world beyond my tax dollars,” he says, and you can almost picture him saying this with a smirk. “Not to sound grim, but when I’m dead I could actually leave the physical sound system in some kind of museum in Guyana or something. Maybe the sound system and its recordings could be part of a permanent installation.

“If some black child or child of colour in high school, growing up in a town like Calgary, came across my work, one of the things I would want them to take away from it is that other worlds are possible.”