Speech sounds are customarily represented by the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), but when Blonk discovered that he was using sounds not represented in the IPA, he created BLIPAX (“Blonk’s IPA extended”) for the notation of his work. The notation eventually inspired “drawings that live somewhere halfway between sound poetry and visual poetry.” The drawings, available online as a free PDF <http://www.jaapblonk.com/OutOfPrint/Traces_of_Speech.pdf> allude to IPA but aren’t necessarily traditionally readable as sound. They retain only traces of speech. So Blonk set about “tracing” them by importing them as raw data into audio software and also running them through optical character recognition software, resulting in German or English texts and electronic sounds which he then used as material to create the seven movements of Traces of Speech (2014). It’s a brilliant and fruitful conceit. What does notation inspire beyond what it is supposed to notate? What is signifer and what is signified? And looking at the images or listening to the music, it’s not always clear what you’re hearing or looking at. Is it human gesture, a transformed gesture, or something else entirely? Blonk weaves an inventive, varied, and surprising polyphony of voice and electronics, including speech, sound poetry, and synthesized computer voice.

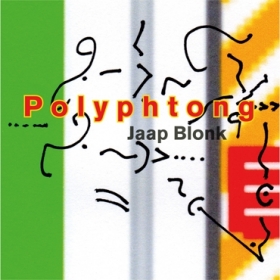

Polyphtong (2013) is a single forty-seven-minute work that unfolds symphonically and is much more intense in conception than the previously discussed works. Originally a quadraphonic piece for live performance, Polyphtong is represented here in a reworked stereo version; spatialization remains a significant compositional element. Though it sets out to explore diphthongs (cf. Polyphtong) and approximants (phonemes, such as “w” between fricatives and vowels)—and all the sounds are, astoundingly, created from Blonk’s vocals—the timbres are wildly varied and often rich, complex, and beautiful. Strata of slowly evolving sustained sounds—breathing, growls, extended phonemes—move tectonically. Flocking textures created of multiple repeating sounds sometimes approach the stochastic conversational interactions of crowds. The rich palette of timbres and textures recalls orchestral, electronic, and ecological sounds.

In these three CDs, ranging from quirky avant-lieder and poetic explorations of synaesthetic semiosis to large-scale works where Blonk becomes a contemporary Bruckner of sound poetry, it’s not just Jaap Blonk’s performances that are virtuosic and remarkable, but his compositional vision.