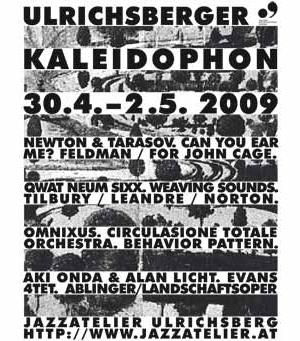

A site-specific performance that took into account the dimensions and machinery of a still-functioning 1853 linen factory, a resounding interface between pulsating electronic and acoustic instruments, and a full-force finale involving a mid-sized band were among the notable performances at 2009’s Ulrichsberger Kaleidophon.

The consistently high quality of the eleven concerts that took place during the twenty-third edition of this three-day festival was remarkable. Equally so was the location: a farming and small manufacturing village of fewer than 7,000 people, about sixty kilometres west of Linz, Austria.

Yet the clutch of top-flight improvisers participating made sure the constant timbral pulsations were as rivetting as the location and the players’ physical strategies. Swiss pianist Jacques Demierre was stationed on one side of the space, abutting an electronic set up encompassing mixing boards and computers manned by technicians. On the opposite side of the factory floor was German synthesizer player Thomas Lehn with his instrument connected to the electrical source for one of the largest machines. On identical raised platforms nearby were French clarinetist/vocalist Isabelle Duthoit and Swiss saxophonist Urs Leimgruber; while Swiss violinist Charlotte Hug and singer/hand saw manipulator Dorothea Schürch created undulating tones and sul ponticello squeaks from positions on the catwalk above the factory floor.

With visual cues difficult, sixty miniature speakers placed strategically around the room enabled players to react to one another’s initiatives. If the warp and woof of their concentrated and jagged tones wasn’t stimulating enough, Demierre at points climbed on the piano bench to cue the operation of one loom. The resulting mechanized clamour of shuddering and screeching, as the colourful cloth was stretched and sliced, meshed seamlessly with fortissimo reed split-tones, cascading synthesizer oscillations, strangled throat spewing, and catgut gashing from the instrumentalists. Perception of particular passages, whether banged out on a keyboard or arched from a reed-player’s bell—as well as of the piece itself—was dependent on proximity, since most audience members changed positions several times throughout the concert.

Spatial issues didn’t figure into the electroacoustic showcase by the French Qwart quartet two days earlier. With tones bouncing off the stone walls of the Jazz Atelier, a former pig barn sturdily constructed in the sixteenth century, baritone saxophonist Daunik Lazro’s circular-breathed growls and tongue stops vibrated so powerfully that he had to change reeds mid-set. Meanwhile, violinist Michael Nick bowed abrasive spiccato, while Sophie Agnel’s timbre extension involved stopped piano keys with the strings weighted by Styrofoam cups and scraped with fishing lines. Providing both crackling and blurry ostinato, plus broken octave expansions of the others’ textures, with electronics that included an e-bow and a camera flash, was Jerome Noetinger. A percussive finale was created by Agnel repeatedly slamming the piano lid.

Precious is an adjective that would never be applied to Norwegian reedist Frode Gjerstad’s 12-piece Circulasione Totale Orchestra, whose sounds blasted the atelier’s rafters for the Kaleidophon’s finale. In addition to having Norton on vibes, the Scandinavian players were augmented by such long-time Gjerstad associates as American Hamid Drake and South African Louis Moholo-Moholo on drums, British bassist Nick Stephens, plus two Americans, reedist Sabir Mateen and cornettist Bobby Bradford. Each helped direct the intensely energetic music away from self-indulgence towards group cohesion.

Adding their strokes and paradiddles to a bottom further solidified by Morten Olsen’s percussion and Lasse Marhaug’s electronics, the non-European drummers built a backdrop impermeable enough to serve equally as foundation for chicken-scratch guitar licks and percussive hand-tapping from the electric bassist, as well as the jagged reed-twisting of Gjerstad and Mateen. Harmonized or alone—and often buoyed contrapuntally by Børre Molstad’s tuba burps or Stevens’ steadying strokes—the reedists zoomed from split tones to multiphonics, advancing improvisations in different pitches. Mateen was as uncompromisingly atonal on his instruments as Gjerstad was on saxophone. He distinguished himself with pastoral flute passages and stressless clarinet trills. Bradford, more iconoclastic still, maintained his modest and melodic composure even when the rest of the band played fortissimo.

Bradford’s molten creativity was cast in boldest relief, however, when the cornettist joined with a clarinet-playing Gjerstad for an encore. With harmonies so soaring that they approached pure song, the unaccompanied duo also batted broken octaves back and forth. These timbres, simultaneously challenging and classic, neatly summed up the sort of unexpected sounds exposed at the annual Ulrichsberger Kaleidophon—and encapsulated the festival’s abiding appeal.