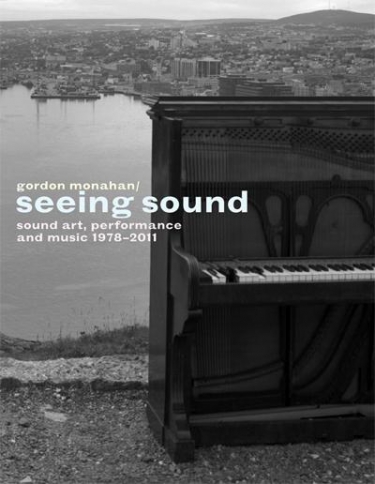

If there is one life-changing moment in the career of the Canadian composer, performer, and sound artist Gordon Monahan, it may well have been his encounter—and eventual partnership—with Laura Kikauka. Leafing through the monograph Seeing Sound, which spans over thirty years of his work as an artist, you will see an image of him wearing a jacket of fiendishly baroque design while reading Liberace’s autobiography. The information this picture conveys is twofold: Monahan knows that presenting art is essentially—and literally—showmanship; and he does not shy away from kitsch. Monahan has always been keenly aware of showmanship, but it was his introduction to Kikauka’s uninhibited tastes that gave his sense of kitsch a new focus and direction. The use of kitcsh has widened the scope of his presentations. On the other hand, there’s always his sense of the spectacular, and an open-minded curiosity that happily embraces unintended results.

Seeing Sound (which comes with a DVD) documents the work and the multifaceted mindset that has created behind the work in satisfying detail, and provides a wonderful introduction through insightful essays and a wide-ranging conversation between Monahan and the legendary Berlin curator Matthias Osterwold. There are the monumental installations, such as the Long Aeolian Piano, in which the wind vibrates fifty-metre-long strings that are connected to the sounding board of an upright piano anchored to a tree. Monahan plucks the strings and heightens their tension by tilting the piano ever so slightly, evidently using considerable physical strength. While the wind makes the strings sing and hum with whistling overtones, plucking them sends deep sonorous twangs back and forth along the wires. These aeolian installations create dense pulsating clouds of sound that hover around the installations like intangible otherworldly shells.

Monahan’s installation A magnet that speaks also attracts, although installed in a largish showcase, is decidedly smaller in scale. It is a semi-automaton that catapults a speaker cone, playing Muzak-like selections from Monahan’s extensive vinyl collection, to a piece of metal overhead. After that, the speaker cone is lowered back onto the catapult. This sequence takes place with a pleasurable degree of noise. Sometimes the cone misses the ladle, and Monahan will have to put things back in order again, by hand.

Monahan’s acceptance of the intangible is a recurring characteristic in his work: he doesn’t need to be in total control. There is room for deviation from the planned course; and that is where unforeseen, and subsequently interesting, things may happen. In When it rains amplified disc-shaped objects on which water drips and gushes produce unpredictable syncopation.

Monahan has gradually become an organizer of sound events. Living in Berlin he made things happen with Kikauka in their Glowing Pickle electronics surplus store. Afterwards they conceived the aptly named Schmalzwald extravaganzas, full of kitschy Muzaky “irritainment”: tongue-in-cheek showmanship, vexing entertainment. And for the past seven years they’ve been conducting more of the same at their Electric Eclectics Festival on the Funny Farm near Meaford, Ontario, where they spend six months of the year. Monahan fully reveals his organizing skills when he combines several of his pieces simultaneously into Space becomes the instrument, a performance that involves an entire concert hall. However disparate the components may be, over a lifetime of work, he has succeeded in forging a credible musical unity.