It’s a typically humming Saturday night at the Tranzac Club. Different events are in progress in each of the Toronto venue’s three rooms. The Tiki Room (the smallest and most living-room-like of the three) is hosting a special edition of the Audiopollination series, which is usually held elsewhere; its regular events are self-curated affairs, where community members simply put their names in an online spreadsheet and collaborate with whoever else has done the same. This special show is taking place offsite to fit the timing of a minitour assembled by Sound of The Mountain’s Elizabeth Millar and Craig Pedersen, regular Audiopollination visitors from Montreal, who have brought a couple of guests with them.

Pedersen and Millar, along with fellow Montrealer Anne-F Jacques, mix with local improvisers during the first three short sets. The closing set features a rare local appearance by Kobe, Japan-based Canadian musician Tim Olive, who is joined by composer and experimental performer Allison Cameron and experimental sounds player William Davison. Before starting, Olive gives a nod to Cameron, as if they are picking up on a paused conversation. That turns out to indeed be the case—although the last time the pair played together was back near the turn of the century when Olive, who was in a phase of minimal quiet improvisation, was touring with percussionist Jeffrey Allport. Some things unfold slowly over time.

“The Tranzac show was a good example of why I like to play with people, and how I enjoy the variety of situations,” Olive tells me a couple of months later in an email. Deepening a dialogue with regular collaborators is central to Olive’s work, but he acknowledges that going out on a limb with less-familiar faces is important, too.

The trio at The Tranzac find common ground in an entrancing set of small electroacoustic gestures, each generating unique acoustic sounds with their instruments and noninstruments: banjo and kalimba for Cameron; toys and a bowed compact disc for Davison; and what is sometimes listed as tabletop guitar (and other times magnetic pickups) for Olive. Over the course of the set, Olive reduces the guitar to its simplest essence; his single string is bowed, blown on, flossed by cassette tape, and flexed by an attached spring whose other end is clenched in his jaw. Though seated between the two other musicians, his soundworld never quite feels front and centre—rather, it acts as more of a connective tissue, creating a space into which the sounds surrounding him can be integrated.

That tendency is a holdover from earlier days as a bass player, first in rock bands (Black Sabbath remains one of Olive’s stated influences) and then in more abstract postpunk units, such as Montreal’s Nimrod, which moved from being somewhere between Scratch Acid and the Butthole Surfers before unfurling into aggro musique concrète with increasing amounts of improvisation. “In my mind I’m still a bass player. I see a direct line from my early bass-playing days to what I’m doing now,” he said in a 2012 interview in The Sound Projector Magazine.

Tim Olive was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, and spent his teenage years in the town of Davidson, due north of Moose Jaw, picking up the bass and playing in bands inspired by Black Sabbath and Rush before heading further north to Saskatoon (the province’s big city) to finish high school and play music. His move to Montreal in the late 1980s was perfectly timed, he says, “because there were a lot of great folks to play with, a lot of venues, and the cost of living was low, so I could work casual part-time jobs and devote the majority of my time to music.”

He was still playing rock at that point, “but it was odd rock, and getting odder all the time.” While playing with the late Zev Asher, his bandmate in Nimrod, Olive spent some time in Osaka and eventually was able to move there. “My first visa was for six months,” he recalls. “I never planned to stay a quarter century.” Asher joined him in Japan, and Nimrod enjoyed its most fruitful creative period there. Ensconced in Japan’s noise scene, the band “started weird and got weirder,” Olive recalls, “improvising more and more, getting less musical. There was a lot of overlap between the edges of the weird rock, noise, and improvised music worlds at that time. I moved very gradually from out-rock to what I’m doing now.”

Olive sees continuities rather than pivots, in terms of his development as a musician, although that steady evolution might not seem so obvious to someone just seeing an occasional show of his or listening to one of his albums in isolation. Some things, as already noted, unfold slowly over time.

That sort of patient dedication to following his own path has consequences, of course. “I realized that I’d never be able to make any kind of a living from music; I decided that to be able to play what I wanted to play I would always need to have some sort of nonmusic income. Being from a small town, with a farm–working-class background and with my formative musical experiences in a D.I.Y.–punk milieu, grants and institutions were something I never thought about. So I knew I would have to live frugally, which included not having children and not owning a house. These kind of life decisions are very important, and often not discussed.”

All these factors have played into Olive’s pragmatic decision to stay in Japan, although he’s not able to say specifically how being there has affected his music. He also reminds me that it’s an outsider’s oversimplification to reduce Japan to a monolithic entity. “I think a major influence has been living in the Kansai region (Osaka / Kyoto / Kobe / Nara) rather than Tokyo. Kansai is not as polished as Tokyo; the weirdo improvised music folks here are very proud of being from Kansai. Maybe it’s a tiny bit like Kansai is Montreal or Chicago and Tokyo is Toronto or New York: the Tokyo folks have the media attention (such as it is) and the infrastructure; Kansai has something else. Takuji Naka, who I’ve been playing, recording, and touring with for several years, says Kansai musicians are like cockroaches: there’s no sunlight, but you can’t kill them, and they never give up. So I think living in Kansai has had an effect. I play in Tokyo and I play with Tokyo folks, but I love the Kansai spirit, the feistiness. There’s a punk–D.I.Y. feeling that I admire. Coming from Saskatchewan, it resonates with me.” [Above photo: Tim Olive and Takuji Naka perform in Taipei, April 2018.]

If Olive isn’t entirely sure how his time in Japan has affected his way of making music (we tossed aside the phrase “artistic practice” early on in our conversation; “that sounds like money,” Olive commented), he is equally unsure how exactly his prairie upbringing shapes him now: “Spending the first two decades of my life on the prairies has shaped me and the music in ways that are hard to verbalize but are real. I know that (painter) Agnes Martin, who was born in Macklin, Saskatchewan, disavowed any geographical influence on her work, but I can’t deny the influence. I don’t want to deny it—the geography, the climate, the plants and animals. I feel it inside somewhere, always.”

But perhaps the confluence of prairie isolation and cultural distance explains Olive’s consistent need to bond with his chosen community. “Collaboration is very important to me. My most important and formative musical experiences—my best musical experiences—have always come from playing with other people. I find it’s so much more enjoyable and surprising and exciting, and fun, to play with others. Something special can happen. And I do like the social aspect. Life is richer with other people.”

Aside from his live shows in Japan and occasional tours abroad, Olive’s penchant for collaboration is also expressed through his label, 845 Audio, which has been, since 2012, his main vehicle for documenting this work. With attention paid to the tactile qualities of a CD, the 845 Audio releases all come in cardboard cases with boldly minimal, woodcut-inspired graphics. When listening to a Tim Olive recording, one might be tempted to pause to double-check that the kettle (or rock tumbler) hasn't been left on. Clangs, pings, rattles, and whines sometimes suggest a gently combative terrain, but that's also countered by the hums and drones of embracing sound-fields.

Most of 845 Audio’s first fourteen releases feature duos, with a couple of trios sprinkled in, all of them instances of something greater than the sum of the parts being generated through musical interaction. Made in Japan, Europe, and Canada, the recordings reveal the diversity in Olive’s soundworld, through his performances with Cristián Alvear, Doreen Girard, Martin Tétreault, Yan Jun, Cal Lyall, Frans de Waard, Takuji Naka, Jin Sangtae, Ben Owen, Anne-F Jacques, Jason Kahn, Katsura Mouri, Alfredo Costa Monteiro, Elizabeth Millar, and Craig Pedersen.

While Olive doesn’t rule out the possibility of releasing solo outings, that seems less important than exploring shared spaces with old and new collaborators, starting new conversations, and picking up old ones where new possibilities have been ripening.

Meanwhile, as the set at the Tranzac ends, old and new conversations of a different kind are ignited as friends in the audience gather around Olive for an impromptu reunion. As he works his way back towards the West Coast (with a stop, of course, in Saskatoon), there will be a shifting tapestry of old friends and collaborators to encounter—in the long haul, Tim Olive has learned to improvise with time and distance in relationships and a dispersed community, as much as in music.

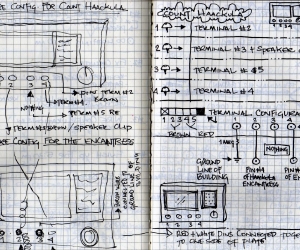

Top photo of Tim Olive and bottom photo of instrument / gear setup taken in Winnpeg, June 2019 by Robert Szkolnicki. Photo of Allison Cameron, Tim Olive, and William Davison at Trazac, Toronto, taken by Joe Strutt. Photo of Tim Olive and Takuji Naka in Taipei taken by Huang Wei. Audio: Boro, excerpt (2019), composed and performed by Tim Olive (magnetic pickups) and Doreen Girard (prepared tsymbaly). From the album Boro.

[CORRECTION: The photo published on pg. 13 of Musicworks 135 (Winter 2019 print issue), and in the table of contents, associated with the article "Tim Olive's Flexible Aesthetic," were misidentified as showing Tim Olive; the photos showed Brendon Ehinger, who performed at the event mentioned in the caption, but at a different time. Musicworks regrets the error and extends its sincere apologizes to Tim Olive and the photographer Robert Szkolnicki. The photo at the top of this story is the image that should have been published on pg. 13 of the issue.]