Canadian composer Taylor Brook—whose music can strike an unusual balance between challenge and charm, sometimes with an astonishing delicacy—had been based since 2011 in New York City, where he was first a doctoral student and then a lecturer at Columbia University, all the while making the most of the city’s wealth of performers. But in 2020, as travel restrictions appeared imminent under global COVID-19 regulations, Brook and his wife relocated with their two young children to British Columbia to be closer to her parents. It would be, he thought, a short stay while the whole virus thing blew over. At the time of our conversation earlier this year, Brook was teaching composition at the University of Victoria in B.C., while maintaining his Columbia commitments online. His new location is more than an additional line on his CV: he has already noted changes in his work brought about by his shift from interacting directly with ensembles in a busy and crowded city to working in seclusion in a much less densely populated environment.

“I find myself drawn toward some almost cliché West Coast ideas—music for large outdoor spaces,” he said. “But more than anything, this pandemic has shaped my thought. I’m not going to concerts; I’m not working with other musicians.”

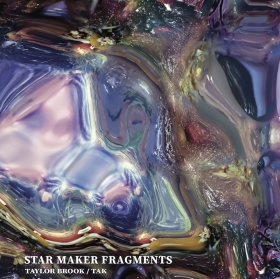

Sense of place is a strong influence in Brook’s work, as are the post-apocalyptic worlds and alternate life forms of the esoteric science-fiction literature he favours. As a student, the Edmonton-born composer moved across Canada, and studied in India and Belgium before landing in New York. “I’ve moved around enough to become pretty aware of how place shapes what I’m interested in,” he said. “In New York, all the groups that I worked with were just so incredible that I could write all this different music, and they could do it seemingly with ease.” Brook began writing more difficult music and tackling bigger ideas while living in New York. Star Maker Fragments is an hour-long piece released in March 2021, recorded by New York’s TAK Ensemble—a contemporary chamber group that has slowly been growing in recognition in the city. The piece is bright but otherworldly, befitting the narration provided by Toronto-born Charlotte Mundy, the ensemble’s soprano. Star Maker Fragments is not the first piece Brook has written specifically for TAK, and it’s not the first piece he has composed with the ensemble in mind. “If any group were to pick up any of these pieces and perform them well, I hope that they would make them their own,” he said. “But when I’m writing, I’m hearing Charlotte.”

The narrative was constructed from the 1937 novel Star Maker by British writer Olaf Stapledon about an earthling explorer discovering life on other planets. Brook sent his excerpts from the novel to Mundy and asked her to record herself reading it, then used her rhythm and inflections as a framework for the piece, transferring her natural cadences onto the piece. The other members of the ensemble were then given their parts to record, and the piece was rehearsed and developed via video conference before the ensemble came together in the studio (while observing the distancing and isolation of 2020) to record it. The album includes an eleven-minute postlude that Brook constructed from the musicians’ first-draft recordings. The whole process created a sonic environment in which Mundy clearly lives comfortably.

“His vocal pieces are so naturally theatrical,” Mundy said. “I really like singing in a theatrical way. Obviously, he doesn’t write gestures for us to do and it’s not necessarily overdramatic, but he has a real sense of storytelling. It feels more like theatre to me than art song.”

Mundy, a founding member of the ensemble, worked with Brook even prior to the group’s formation, having performed his Five Weather Reports, a piece TAK included on its first album, Ecstatic Music—TAK plays Brook. The ensemble included a piece by Brook in its first concert and Brook has since come to work with TAK in a more formal capacity as its technical advisor. The challenges in his music have been an education, according to Mundy.

“I really appreciate the system he uses for notating microtonal music,” she said. “I feel Taylor really shaped how I learned to sing microtonally.”

Star Maker Fragments might be called chamber psychedelia, an imagining of other worlds in a narrative that works on a subconscious level. There’s no real through line, and Mundy’s voice is sometimes subsumed in the music, but the feeling of discovery by searching through darkness is palpable. Star Maker novelist Stapledon was an ethicist who spoke and published widely on pacifism and the need for global government. While the storyline isn’t preserved in Brook’s treatment of the novel, its moral underpinnings are still present and thought-provoking.

Brook said the novel speaks to many of today’s conflicts and he hopes that his treatment “opens up possibilities of self-reflection in certain areas. I definitely believe that the only way to learn or change is by an internal realization.

“I’m hoping that the pieces that I’m making are self-contained,” he added. “It’s not just referring to the text. I think of the pieces as self-contained things.”

The American writer David Ohle’s 1972 novel Motorman has served as inspiration for a couple of Brook’s compositions already, and he has plans to set the entire novel, which author Shirley Jackson, writing in Book Forum, said “closes the gap between the representation of a disturbing thing and the thing itself. You feel you ought to wash your hands after touching the page.” Brook has cast the post-apocalyptic novel in Motorman Fragments (2011), for four voices, percussion, cello, guitar, and clarinet, and Motorman Sextet (2013), for six voices. Both have been performed by the New York vocal ensemble Ekmeles.

“Motorman is kind of halfway between traditional science fiction and William S. Burroughs,” Brook said. “It’s got kind of a grotesque twist to it and an absurdist twist to it.”

While Brook has written for large and small ensembles, solos, and duos, and for instruments with electronics, the voice has been a recurring interest—even when the piece is not to be sung. His Vocalise (2008), for violin and drone—which he considers his first real piece —was informed by his study of Hindustani music. “I didn’t want to write something in that style, but I was interested in taking some of the formal ideas and bringing them to the instrument,” he said. He mirrored the structure of traditional Hindustani composition, but had the melody line gradually descend rather than ascend. Song (2015) is for solo cello, based on vocal multiphonics.

Born in Edmonton in 1985, Brook grew up in Toronto, picking up guitar at age ten and violin at twelve. As a high-school student at the Etobicoke School for the Arts, he was inspired to pursue composition after hearing the St. Lawrence String Quartet play Bartók’s String Quartet No. 4. He went on to major in composition and classical guitar at McGill University’s Schulich School of Music in Montreal, where he had his first public performance of a work—a piece for soprano titled Knowledge Believes Memory—in 2009. A setting of a text by Faulkner, the piece was written for a student concert organized in conjunction with production of Stockhausen’s vocal sextet Stimmung. He now considers his effort then to be a bit of juvenilia in which he was trying to consider microtones, but it was an early marker for his interest in vocal music.

He continued his studies in summer programs at the Domaine Forget de Charlevoix International Music and Dance Academy and the National Arts Centre of Canada, and travelled to Kolkata in the India state of West Bengal to study Hindustani music for two months before returning to McGill for a master’s in composition. After completing the program, he was awarded a Personal Project Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts to study composition in Brussels with Luc Brewaeys and received a commission from the Banff Centre for the Arts. Montreal-based Quatuor Bozzini included his 2011 composition Florescences on their album À chacun sa miniature, the first commercial recording of one of his compositions. That same year, he enrolled as a doctoral candidate at Columbia, where he studied under Richard Carrick, Georg Frederich Hass, and George Lewis.

Somewhere along the line, he lost track of the guitar, a situation only rectified under the seclusion of life in Victoria. He picked up a Telecaster and started playing in open tunings, putting his improvisations through a Max/MSP patch he wrote that analyzes pitch, brightness, loudness, and harmony and responds to them with its own sonic contributions. “You sort of train it,” he said. “You play, it listens, and at a certain point you tell it it’s ready.”

Eventually, the AI collaboration came to be Apperceptions, his latest recording (available as CD or download and streaming in full on Bandcamp). It’s a relaxed and spacious listen, clocking in at over ninety minutes, with hovering notes that might bring Bill Frisell to mind. It is, in other words, rather different than the oddball dystopias of his recent work, closer (cliché or not) to the wide-open spaces of the West—and the ways one might understand those lands. Or perhaps the ways musicians might understand themselves, be they cyber or anthro.

In an email following our video-conference interview, Brook offered: “I was trying to think of a title that related to the improvised or spontaneous nature of the music, both from my perspective and that of the computer improviser, and I came across this word (apperception) and found the [Oxford English Dictionary] definition to be quite rich: ‘the mental process by which a person makes sense of an idea by assimilating it to the body of ideas he or she already possesses’ or ‘fully conscious perception.’

“This definition described what I was doing with my improvisations in this piece—especially the first definition. And then for the computer improviser, I also felt like the definition related to the way the improviser functions by relying on generating new material from an audio corpus that it has learned from.”

The Max/MSP patch has taken on some other gigs of late, as well. It collaborated with a cellist—with Brook making small, real-time adjustments—for a virtual concert marking the tenth anniversary of McGill’s Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music Media and Technology. Meanwhile, Brook has been collaborating with violist Marina Thibeault, who teachers at the University of British Columbia’s School of Music, on a sinfonietta that will address the traumatic births of each of their children, and that is to be performed by UBC’s Turning Point Ensemble.

“We thought this piece might even be appropriate for a hospital setting,” he said, imagining a possible workshop version that would incorporate communal breathing exercises.

He acknowledged, though, that—like many of his compositions—there might be limited performance opportunities.

“I can’t help but think that most ensembles, when they open my scores and see all the microtones, close them up again.”

Learn more about Taylor Brook here.

Read Kurt Gottschalk's review of Star Maker Fragments for Musicworks here.

PHOTOS: Photos of Taylor Brook by Carly Levin.

FYI: Taylor Brook is one of four University of Victoria recipients of the prestigious Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship. As part of his research-creation project, he will be writing a new composition for the Victoria-based Aventa Ensemble, to be performed in 2023.

ON THE CD: Virtutes Occultae, excerpt.