Billed as the AGO’s “first hip-hop exhibit" in its 124th year of existence, The Culture can be viewed either as a cause for celebration—given hip-hop culture’s reign as the leading art form du jour—or as a source of embarrassment, given that this is hip-hop’s fifty-first year of existence. Why present a travelling American hip-hop exhibit, and why now? And can an Ontario-based gallery properly represent local hip-hop artistic output underneath a juggernaut U.S. hip-hop art show umbrella, given the AGO’s local curator Julie Crooks’ organizational stamp on the exhibit?

The Culture—which is co-curated by the Baltimore Museum of Art’s Asma Naeem and Gamynne Guillotte and the Saint Louis Art Museum’s Andréa Purnell and Hannah Klemm—opened in 2023 as a travelling art exhibition marking hip-hop’s fiftieth anniversary commemoration, yet it still feels timely and topical, given the ubiquitous nature of a culture that has captured the imagination of Gen Now to Gen X (and Baby Boomers, too). Deftly organized into six distinct sections—Ascension, Pose, Language, Adornment, Brand, and Tribute—the exhibition is a bird’s eye view of the myriad ways hip-hop culture has been a mirror to reality, showcasing some of the celebratory and inflammatory aspects of modern life. More than one hundred pieces of artwork—paintings, photography, sculptures, AV work, fashion displays, and immersive installations created by more than sixty-five artists—are underscored with ambient soundscapes created by musician, producer, and hip-hop scholar Wendel Patrick and featuring music from St. Louis and Baltimore artists mixed with that of notable Toronto acts like Tara Chase and Choclair.

At least two dozen, if not more, pieces make The Culture worth the cost of admission. One standout is the gorgeous eight-minute “4:44” video produced by the Afrocentric TNEG motion film studio (Malik Sayeed, Arthur Jafa, Elissa Blount Moorhead) comprising two performances: a gripping, twisting choreographic number by renowned dancers Okwui Okpokwasili and Storyboard P, and a Jay-Z and Beyoncé audiovisual piece that sees them serenading one another in response to the former’s infidelity charges, all played out over Jay-Z’s track of the same title. Likewise, filmmaker Kahlil Joseph’s breathtaking two-channel, fifteen-minute video, which uses Kendrick “Not Like Us” Lamar’s 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city as the soundtrack, takes the viewer through a moving day in the life of a Compton, California resident. The exhibit’s slam dunk installation is St. Louis-born sculptor Aaron Fowler’s “Live Culture Force 1’s 2022,” an enormous pair of Nike Air Force 1 shoes made out of recycled car parts and found materials, strategically placed in the centre of the gallery’s main room. The piece essentially centres the exhibition and performs this uniquely hip-hoppy psychological dance of merging the sublime (Fowler produced the piece to honour his cousin, who died in a car crash) with pop culture chic (wearing Air Force 1 shoes is a staple of hip-hop culture).

Some of the exhibition’s Branding component lacks depth: The fashion section features a hodgepodge of clothing items from pertinent hip-hop streetwear lines like Baby Phat and Too Black Guys slapped onto mannequins; likewise, the Moncler “Maya Jacket” full-room display of the red bubble jacket Drake popularized in the viral “Hotline Bling” music video felt like an unnecessary and artless inclusion—perhaps set up to appease contemporary rap audiences with an affinity for rap music’s leading man. However, the original old-school “buffalo hat” designed by Vivienne Westwood and re-popularized by Pharrell and the Dapper Dan/Gucci leather jacket collabs driven by the tensions between the high-art fashion world and the streets rescued that section.

Given that this was the first time the AGO has fully dipped into the hip-hop art waters, the CanCon add-on pieces didn’t add much to the original travelling exhibit, beyond feeling like an obligatory nationalistic chest-thumping ritual. Elsewhere, legendary Canadian photographer Patrick Nichols had been commissioned to create a large original photo, featuring 103 Canadian hip-hop scenesters, channelling an overplayed motif of Art Kane’s famous 1958 photo “A Great Day in Harlem.” No thorough explanation is given as to the criteria for the people included in the Toronto version of “A Great Day In”; iconic local hip-hop innovators and practitioners such as Drake, Maestro, Kardinal Offishall, k-os, Director X, K’naan, K-4ce, and Ivan Berry aren’t in the photo, but reggae icon Snow is. The first words in my book Hip Hop World are “It’s a hip-hop world, and you are just living in it,” and the exhibit lays out in clear view the far-reaching influence of hip-hop culture on modern-day style codes—from the durag-inspired art of John Edmonds and Anthony Olubunmi Akinbola to the jewelry-laced output of Robert Pruitt and Bruno Baptistelli, all the way over to the carefully curated selections from rapper Lil’ Kim’s wig collection. When you combine these countercultural stimuli, mixed in with some classic Carrie Mae Weems and Hank Willis Thomas portraiture, The Culture clearly fulfills its purpose.

TOP PHOTO: Patrick Nichols, Michie 2K, 2000.

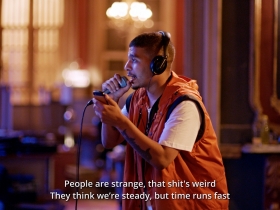

BOTTOM PHOTO: Stan Douglas, film still from ISDN, 2022. Two-channel video projection.