As the result of a string of reissues at the beginning of 2004, Arthur Russell has risen to posthumous prominence as a ravenous pluralist and unsung innovator who did not achieve due recognition prior to his untimely death from AIDS in 1992. With each re-pressing or unreleased gem it becomes increasingly clear how intriguing, enduringly relevant, and singular his work was, despite his involvement in such a disparate array of musical activity.

While alive, Russell was on the periphery of each of the scenes with which he was superficially affiliated. While some of his dance tracks were touted by the most important disco DJs—Larry Levan, Nicky Siano, and Walter Gibbons—other tracks were too dissonant or delicate for the dance floor. Though he was curator of the Kitchen, and was celebrated among some of the most pivotal downtown figures, including Philip Glass, his more experimental left-field ensemble pieces were too tentative and fey to match the more brazen aesthetic favoured across the Downtown avant-rock and new-composition scenes of the day. Despite their depth and beauty, his ethereal cello-and-voice songs were too transparent and intangible for him to become a part of the singer-songwriter world.

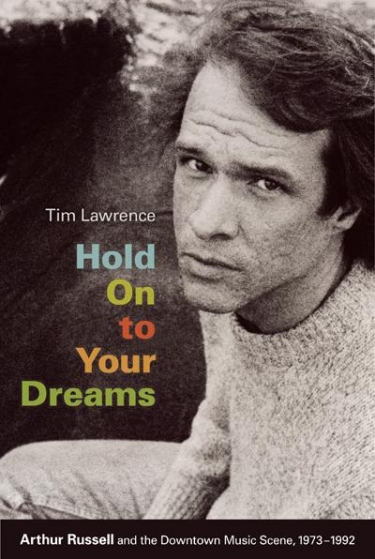

Some journalists and, even to an extent, the Russell documentary Wild Combination, tend to eulogize the spiritual and otherworldly aspects of Russell and his music, to the exclusion of all else. Tim Lawrence’s portrait, however, captures Russell’s idiosyncratic, complex, and contradictory nature in vivid detail. Lawrence paints Russell not just as the mystical-cello-sage-cum-disco-Buddhist, but also the shy, stubbornly opaque, restless individual who could be as befuddlingly aloof as he was musically gifted. Hold On To Your Dreams casts light on the true breadth of his vision by also charting his various false starts, one-off collaborations (who would’ve imagined Russell collaborating with Vin Diesel, who was then a budding rapper?), and chance meetings. It also endeavours to reconcile the seemingly polarized musical worlds inhabited by its subject.

Moreover, while Hold On To Your Dreams does offer a yet-unforeseen full picture of Arthur Russell himself, it uses its subject as a foggy lens through which to glimpse the cultural climate of New York City during one of the most crucial and artistically vibrant eras. Lawrence, drawing on the engagingly fragmentary style of his excellent critical evaluation of disco, Love Saves The Day, carefully situates us within the landscape that informed Russell’s work, and which Russell gently informed as well. Never one to essentialize or oversimplify though, Lawrence also is careful to trace the complex, and decidedly Downtown, network in which Russell participated. He mounts a critique of the Downtown scene, which for all its pluralism somehow didn’t manage to fully grasp the more delicate sensibilities of the cellist.

One is left with the impression that this critical appraisal of Russell’s work is long overdue. Though thoughtfully cautious about such narratives, Lawrence makes a cogent, if appropriately idiosyncratic, case for inducting Russell into the list of brilliant American maverick musicians.