In the spring of 2018, Chinese archeologists announced that they’d unearthed a four-thousand-year-old collection of jaw harps (kouxian in Chinese) at the Shimao ruins, a prehistoric site in Shenmu City in northwest China’s Shaanxi Province.

These artifacts, which were carved from bone, are the oldest jaw harps ever discovered, but various historic versions of the instrument and references to it continue to be found all over the globe. The puny jaw harp, it would seem, is one of our most ancient and pancultural musical tools. Few instruments beyond the Palaeolithic-era bone flute and the human voice itself are more ubiquitous and primeval.

Though today most jaw harps are constructed of metal, not bone, the mechanics have changed little over millennia. It’s a simple device, consisting only of a flexible reed running between two stationary tongs. The tongs are placed against the top and bottom front teeth, which are kept slightly open, and the end of the reed (the trigger) is plucked with the thumb or a finger of the free hand. The subsequent springing motion of the reed in and out of the mouth produces the root of the instrument’s sound. But the performer’s body, in particular the mouth and throat, acts as a resonating chamber, amplifying the reed’s minute vibrations. Subtle changes to the shape of the oral cavity, tongue movements, and manipulations of the glottis, breath, and vocal cords dramatically affect the tones produced. Through years of practice, the mouth and throat of the jaw harpist stretch and form to the demands of the instrument, thus allowing for ever greater dynamics and a richer experience while playing.

Musicologists categorize the jaw harp as a lamellophone, meaning an instrument containing one or more fixed reeds (or tongues) that are plucked or depressed to make sound. Other examples of lamellophones include mechanical music boxes and African mbiras or thumb pianos; certain tongued steel drums may belong to this category as well. The jaw harp, however, is the simplest instrument of them all. Jaw harps are typically capable of playing just a single note (harps come both tuned and untuned), but numerous overtones are achievable. The rhythmic and textural possibilities are also plentiful. And given ample time with the instrument, the wayward jaw-harp enthusiast may even discover that such possibilities go well beyond sound.

A decade ago, my wife’s best friend gave me a toy jaw harp for my birthday. Needless to say, I really got into it! I started cruising the recently revamped, geocities-style Jaw Harp Guild Web site, where I read articles by old-timey jaw-harp educators like Wayland Harman and Michael Wright. I found a tiny festival, a newsletter called “The Pluck-N-Post,” and makers from all over the world. There exists a fledging international community—a diverse array of people trying to revitalize this antique and obscure instrument. I soon discovered recordings: folk and traditional jaw-harp music from Siberia, Central Russia, Germany, England, France, Hungary, and the American South. I started listening for the harp in Ennio Morricone scores and on my daughter’s favourite cartoon shows, too. The breadth and scope of this instrument is incredible. I’d soon discover jaw harpists from the musical avant-garde as well—most notably American Daniel Higgs and Anton Bruhin from Switzerland, two players whose influence can be heard on my early recordings as chik white.

All this to say that I’ve been captivated by the instrument—obsessed, even—since I got that toy jaw harp: the riddle of limitation that each harp poses; that queasy sensation of the reed buzzing between my teeth; how a jaw harp will reflect and merge with nature—building a bridge of sound between perception and the outer world; indeed, that stabbing tone, both uncomfortable and commanding, has for thousands of years been touted as a way to conjure spirits, communicate with animals, heal the ill, and cast spells. Perhaps such claims are nonsense, but when I’m lost with a harp, when time has yielded to that metallic voice reverberating inside my skull, I fully believe in the jaw harp’s exceptional powers.

My enchantment with this simple tool has probably seemed silly to those closest to me—in particular, my wife Sheryl. The jaw harp, I’ve been told, has changed my personality for better and for worse. It’s turned me inward; I know that. And growing old plucking away at these things has changed my body, too—perhaps even hastened my physical disintegration. I am coming undone.

I give my jaw harps names.

Clipping

A Russian-made jaw harp, razor sharp, it is in most ways unlike the others—the ones made in Europe and America. Thick stainless steel, squared edges, two rivets to hold the reed to the frame, and a circular base shaped in an emblem of a two-headed axe. There is strength in its design, sure, but Clipping’s most defining characteristics are its volume and timbre. Certain accentuations with my mouth, like forcefully twisting my tongue into my hard palette mid-pluck, cause Clipping to ring loudly with an otherworldly sustain. I have become addicted to these unusual utterances, and so find myself forcing increasingly uncomfortable facial expressions, chasing after these peculiar sounds and the sensations they create.

Serpent Finger

A mystery harp. I really don’t know where it came from. Until recently I avoided this harp because it’s the most demanding in my collection to play. The reed is firm. It’s hard to pull back, but for this reason, its tone is loud and resonates for an extended moment after the trigger is released. Perhaps the most defining feature of this harp, however, is the way it creates sustain. An incredible suction builds in my chest while playing, rushing air through the harp and down my windpipe. The result is a long, droning tone that numbs my face and turns my legs to rubber. When I am physically unable to take more wind into my lungs, when I feel on the edge of losing consciousness, unable to hold my breath any longer, I force an exhalation, spewing saliva across the reed. It’s beautiful, really, the sound of that bodily fluid moving through the metal, merging with the harp’s already ominous tone. Yes, given some effort, Serpent Finger is a wonder to play, but the peculiar gray metal from which it was crafted is starting to leave black smudges on my front teeth and tongue.

Biter

At less than five centimetres long, Biter is my smallest harp; silver, stainless steel, a German design. Like Clipping, the tongs on Biter taper to a razor-thin edge where they meet the reed. Also like Clipping, Biter is loud, with a shrill tone, though its voice is higher-pitched (my highest-pitched harp, in fact). Interestingly, I didn’t appreciate this harp until I got Clipping. I found it too aggressive; it hurt my ears. So, over the last few years I’ve taken to playing it on my lips—not my teeth—as a way to dampen the tone. Hence its name—The Biter. Once a month, I scrub away the dried blood with steel wool.

Bent High Crawler

A midrange Hungarian harp that has changed in sound and functionality since I acquired it over eight years ago, its reed is much lighter than that of any other harp I’ve owned, so initially Bent High Crawler’s voice was delicate and had a dynamic sense of levity. The reed trigger isn’t looped, which means it’s a bit tricky to handle; nonetheless, I’d become quite proficient at rapid-fire, front-of-finger / back-of-finger plucking in my first years with this harp. Over time, the delicate reed has bent slightly towards the upper tong. As a result, the harp now offers the option of being played completely with breath, unplucked. Though Bent High Crawler’s earlier dynamism is not as easy to attain as it once was (now it mostly sounds clinky and shallow-bodied when plucked), a gentle exhalation of air from my lungs will coax out a pleasing tone that I can manipulate in subtle ways. But there’s a worrisome issue: of all my harps, Bent High Crawler gives off the strongest taste of metal. This harp is supposedly made of stainless steel, but the surface is black and greasy with what the maker calls a “nickel polish.” I’ve become increasingly concerned that the bitter saliva I swallow while playing is poisonous.

Meek German

A standard European harp with a reliable timbre; more of a subtle twang than a springy shockwave with each pluck; a smooth, midrange draw; pronounced but basic dynamics; Meek German, called that for its quiet and narrow voice, was the first harp I acquired after the birthday toy harp. I still play it every few days. Because of its low volume, I started making noises with my throat to complement the harp’s timid song. These vocalizations have evolved with time. Now it’s as if Meek German tosses a hook into my gizzard and snags my vocal cords—plays me like a fish on a line, a sickening sensation. If I’m being honest, I’d say that the music I make with Meek German these days sounds . . . well, diseased. In fact, I wonder if it’s music at all.

Low Gross Talk

My other Hungarian harp, Low Gross Talk, is built in a similar way to its higher-pitched cousin, Bent High Crawler—made of stainless steel and finished with that bitter-tasting nickel plating. Also like Bent High Crawler, the trigger is tapered, not looped. The only difference between the two is their respective lengths. Low Gross Talk is twelve centimetres long, which means the reed is also long and swings wide. These mechanics give it a quiet, very low-pitched voice. As I do with Meek German, I’ve begun making utterances from my throat while playing this harp. Gargling into Low Gross Talk like a fool does take a certain kind of humility and shamelessness. But the results sound sublime to my ear.

Deep Clipping

A beautiful silver object, as big as my hand; looks like a dagger, and often has blood and pieces of skin dried on the tip. This is my other Russian harp and by far my largest and most powerful instrument. The bass note roar with each pull of Deep Clipping’s reed short-circuits my eyes. I go completely blank. This harp is addictive and dangerous. My speaking voice, for example, becomes hoarse and broken for hours after I play it. The reed cuts the insides of my cheeks and causes my top and bottom front teeth to throb. Deep Clipping came in a purple leather sheath with a leather cord attached. I wear it around my neck, under my shirt. It’s heavy. It bounces on my sternum when I walk and bruises the skin. I’m always sore there—still, I wear it most of the time. On the front of the harp sheath is a pea-sized magnetic ball housed in a metal ring. This ball is meant to sit in the small loop at the tip of the harp’s trigger. The weight of the magnet drops the pitch of the instrument to a guttural low. When I play it this way my bowels rumble

and I often become nauseous.

Tools

Over the years, I have developed various unusual techniques to prepare the instruments. I clamp binder clips of various widths and weights to the reeds. I play Biter with a thimble on the index finger of the hand that holds the harp in my mouth; when I pull the trigger with the thimble to the reed and exhale with all my power, the harp sounds as if it’s electrocuting me. While slumped over, drooling through Low Gross Talk, I sometimes hold in my trigger hand a rusty chain that I found on the beach; the jingle-jangle creates a delicate accompaniment to my quiet improvisations (though I think the rusty metal gets into my mouth and causes my stomach to ache). I also use Deep Clipping’s tiny magnetic ball with the other harps; subtle changes in the ball’s attached position affect the dynamics of a given harp’s tone, often in ways that are unpredictable.

When I perform or record, I use a homemade throat microphone, which is basically a black elastic collar with a Loonie-sized contact mike sewn inside. I strap it around my neck so that the mike face presses into the side of my windpipe. I experimented a lot with the placement; it turns out that the side of my throat moves less than the front, which means less extraneous skin-friction sound from the microphone. The only trick with the throat mike is to strap it tight. The harder that microphone digs into my throat, the richer and more bass heavy the sounds. A piece will often end only because I get too dizzy from choking myself to continue. But I’m learning how to hang on, to keep plucking while turning blue.

When I play jaw harp with the throat mike and headphones both on, I hear a music outside my control, sounds from another realm. To say I feel disembodied with that collar strapped on tight is no embellishment. Yet those tones and textures spring from deep within the core of my body—strange gasping noises and begotten rhythms, the slight chokes and squelches, frail voices. It’s like nothing I’ve heard before. For hours, I listen to what these harps tease from the depths of my body, amazed, not wanting this dive inward to ever reach bottom.

But jaw harp is not all magic.

The skin behind my two front teeth, for example, sometimes rubs raw and becomes sore. My teeth ache into my eyes. This can last for days. When the pain is at its worst, I avoid food and try not to part my lips. Keeping a pool of saliva at the front of my mouth tends to ease the discomfort as well. I’m not sure why it happens, though I know it must have something to do with the harps. Perhaps those heavy vibrations from the metal tongs damage the nerves in my soft tissue. The gums, I assume, can only be shaken to the core so many millions of times before they start to die.

My top two front teeth are both fake, up to tiny nubs at the roots. Maybe that’s why I’m able to play jaw harp well—I feel nothing when I pull the reed. My left front tooth was smashed out in a skating accident when I was ten. The right tooth I dislodged with a microphone while screaming in a punk band a lifetime ago. Both teeth were replaced with porcelain veneers. The oldest one, built thirty years back, is now a translucent gray colour and filled with a spiderweb of hairline cracks. The other is headed in the same direction, but still has a bit of milky vibrancy left. I’m sure when people look closely at my face, they assume that I’m destroying my mouth with those rusty harps. Visible wear on these teeth, I’m told, is to be expected. I keep looking at prices for crowns. I want gold or maybe a single steel plate to replace both teeth—to show full commitment to my craft. My wife says no.

The rest of my teeth are chipped, split, and/or filled with grey mercury composite. There are unusually wide gaps between some of my molars on the top, and a few of them are twisted in such a way that they don’t line up with the others. (My orthodontist was a disorganized drug addict who died of an overdose halfway through my three years with braces; his poor workmanship lives on.)

The same punk-band bullshit that took my tooth also destroyed my throat. I used to scream with all my heart through shitty PA systems across the country. Veins would pop out of my forehead and neck. Phlegm would fly out across the audience. And yet, despite all that effort, my natural voice was very weak. No amount of effort could change that, but my vocal cords could really take a beating. If we happened to be on tour, playing every night, I would never talk except while hollering on stage. When I’d get home, at least a week would pass before anything beyond an indecipherable whisper issued from my mouth. Years have gone by since I performed in that band, but the damage is still there. When I play jaw harp, I conjure up the tonal residue of all that scarring in my throat. Using my glottis and my tongue, I make myself sound sick and broken. A unique and, I imagine, disturbing aural experience for my listeners. At least I aim for it to be.

I cough occasionally after playing (and while I’m playing). My lungs burn in spots too, likely from all the hyperventilating and gasping. And I often have a sore throat. Late at night, I take out my wife’s magnifying mirror and examine my mouth. Even when my uvula is throbbing, and swallowing hurts so badly that it takes my breath away, everything looks fine. In my weakest moments, I hawk mucus from my lungs into the sink and examine it with the light from my phone for discoloration or minute shards of metal.

Many of my jaw harps are as sharp as blades, so I often get cut, both inside and outside of my mouth. In fact, it now happens so often that I carry a small blue rag in my harp sack for wiping away the blood. Though I do slice my tongue and inner cheeks on occasion, most of the damage occurs on my lips. So, over the years, scar tissue has built up in that area, especially on my bottom lip, which is disproportionately fat, and thus easily gets in the way when I’m playing. I seem to bleed more easily each time I pick up a harp. I don’t mind the blood. In fact, when I taste it, I get the sense that this music has meaning. And hell, blood can be a particularly evocative piece of theatre during a live performance. The first time I played for an audience, my set ended when a woman interrupted me to ask if I was bleeding (I was delighted to capture her comment on my recorder). During a recent performance at a proper theatre, a venue usually reserved for the local symphony, I was bleeding so badly after the second song that I was dripping blood onto the white stage floor. I watched it pool as I plucked away. I could barely grasp the harp because my hand was so slicked in the stuff. At that show my teeth felt odd too, like I’d cracked one of them. And I had the throat microphone strapped snug around my neck, so on top of all the blood and my tooth problem, I felt dizzy. After that show I started bringing a small mirror on stage with me so that I could always assess my physical state in real time. Wondering about what the audience was seeing that night broke my concentration and made me tense.

Gory soft-seat concerts aside, bleeding is generally fine by me. But I do worry about what toxins are getting into my body by way of these wounds. The metal from which some of these harps have been forged may not be of the highest quality. My latest acquisitions, the two Russian harps, are made of stainless steel. So I assume they are no more noxious to put in my mouth than a fork or a knife. I am unsure, however, what my older harps are made of. The metal of these harps is eroding and being absorbed, I assume, by my body. The two Hungarian harps with the greasy nickel plating are rusting, and the black colour has been changing to a puke green where the tongs come in contact with my teeth. Another of the older harps, the mysterious Serpent Finger, with its dull, rough silver, tastes bitterer each time I place it against my teeth. If I play it too long, my stomach hurts. Whatever toxins seep from all these corroding metals must now be fully part of me, part of my tissue. I suppose it goes both ways though; it’s the fluids of my body and friction of my teeth that have helped undo the chemical bonds of these harps over time. My harps are part me as well.

Flesh morphing metal. Metal morphing flesh.

At first, however, I fought the metamorphosis. I told my doctor about the unpredictable pains in my chest and neck, how nightmares were becoming more frequent, my vision blurring, going flush. I told her about the ringing sound I was starting to hear. She sent me for blood tests and a lung scan. Perfectly healthy. I’ve gone to the dentist to check on changes in my mouth—masses under the skin, painful sensations in my teeth, the feeling that my tongue has disappeared. “Regular anatomy,” she’d always say. “The jaw harps aren’t causing you any problems at all.”

My harps are eating away at me, I have no doubt: guiding changes in my bone and tissue, and even in the ways my brain functions. I am learning to embrace it, to embrace art, that taste of metal always on my tongue, the incredible compulsion I have to pull the reed. I take a jaw harp everywhere I go. And all day, I talk to myself through waves of sound awash in my saliva and my blood.

FYI: chik white’s latest solo album, guts magnet sea, is out now on Kraak Records. He also has a number of collaborative releases on the way, including a split with Toronto-based improviser Xuan Ye.

AUDIO: Vegetable Memory by chik white (Darcy Spidle).

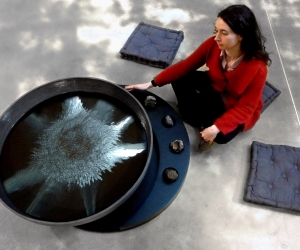

ALL PHOTOS BY HEATHER RAPPARD