SHOULD YOU EVER FIND YOURSELF IN A CONFINED SPACE WITH ERIN GEE, PREPARE TO BE ENTERTAINED, AND PERHAPS ALSO PUZZLED—AT LEAST BRIEFLY.

“If someone meets me in an elevator,” she tells Musicworks in a telephone interview from her office in downtown Montreal, “my elevator pitch is that I explore the communicative potential of the human voice in electronic bodies—and conversely, electronic voices in human bodies. So what becomes a body and what becomes a voice almost becomes a philosophical question, one that has allowed me to really expand the kinds of ways that I explore, ‘What is the score, what are the media, what is the content, in this kind of McLuhanesque, medium-is-the-message kind of thing?’

“I mean, honestly, every time I do a new project, I first think about what would be really fun, and then I learn the media as I go,” Gee continues. “It’s just kind of a new way for me to explore how humans communicate nowadays. So much of our human voices are diffused through telephones, like you and me right now, and through emails and text messages and Skype . . . Really, we swap out our human bodies for electric ones all the time. But I take this to these sometimes ridiculous, sometimes apocalyptic, sometimes beautiful extremes.”

One particular area of puzzlement should be cleared up right now: Montreal’s Erin Gee is not to be confused with the Illinois-based Erin E. Gee, who also sings, composes contemporary music, holds an academic position, and is interested in theatricalizing the concert experience. The Canadian Gee, however, bills herself as an artist rather than a musician or composer, and while sound plays a central role in her practice, it shares focus with new media and performance art.

Much the same can be said of her academic responsibilities at Concordia University.

“I teach sound,” she explains. “But what’s really fun is that it’s in Communications. We listen to classic sound art; we listen to music compositions; we listen to Cage; but what I like is that I can give all this material to my students with a bit of a raised eyebrow, and be like ‘So what do you think about that?’ In my classroom we have people who want to make documentaries, we have people that want to make beats, we have people that want to make weird sound art, and I have to accommodate them all . . . Form almost becomes the only thing we can talk about. Like, ‘Where is the climax? Where are the peaks? Where are the valleys?’ And that’s because I need to somehow compare the narrative arc of an app for running with whatever have you.”

Gee loves what she calls the “interdisciplinary strangeness” of teaching sound to Communications students—and that description serves as an equally useful summation of her own work.

Consider Song of Seven, a work for seven voices and electronics, commissioned by the Hamilton Children’s Choir. In it, the young singers are encouraged, in turn, to deliver a revealing story about their own lives, while the other vocalists improvise a response. That in itself might be a useful and empowering exercise, but the technological hook is that all seven singers are connected to machines that analyze their heart rates and galvanic skin responses—more colloquially known as sweat production—with that data then being transformed into electronic sound.

“I was kind of thinking to myself, Can we put empathy into a choir? Does it even work? And I think it did,” Gee says. “Each choir member had their own note in a harmonic series that would kind of flare up or flare down depending on how much sweat they had. I really just wanted to implicate the bodies of the choristers in the music, somehow.”

Gee notes that much of her work is about “discovering the language of the body,” with sweat her favourite yardstick.

“Your sweat bursts when you’re amused, or interested, or engaged,” she explains, “and if you laugh, your sweat just goes crazy. So I would find myself testing my circuits by trying to force myself to laugh. If you’re just sitting there going ‘ha-ha-ha-ha’ your sweat won’t burst. So I would have to sit there and do pathetic fake laughter. Only when I thought I was a true loser, laughing to my computer by myself, could I test my experiment, because that’s when I would laugh for real.”

“It’s super simple, the way it works,” she continues. “You just send a very, very low voltage through two kind of pads on the skin. Your fingers actually complete the circuit—two different fingers—and how inductive your fingers are depends on how sweaty you are, because liquid conveys the electrical signals more strongly. It’s really, really a basic, never-screws-up signal, and that’s why I’m so interested in it. You’re either sweaty or you’re not, and sweat doesn’t lie.”

Gee explores breath, another marker of emotion, in Echo Grey, receiving its world premiere by singer-composer Andrea Young’s EXO/ENDO ensemble and the Ilk choir in November 2016. The breath itself is an indicator of body function, and it can be altered—and then monitored—without electronic intervention. All one has to do is listen. “I’ve basically set up a lot of musical patterns for the singers to engage with, almost purposely trying to make them hyperventilate,” Gee says. “The magic, for me, happens when the body fails and they can’t do it any more, because suddenly they’re going to gasp for breath. I thought ‘Yeah! This is something I want. I want people to have this human experience with the performers on the stage.’

“The impossibility of the music is what allows you to hear the body,” she adds.

Other elements in the new piece include a microphone inside one of the musicians’ mouths, which will generate feedback, and a glitch-based tape component made by bouncing data between Audacity and Photoshop over and over. The overall effect, Gee says, is dense yet monochromatic; hence the “Grey” in the work’s title. “Echo,” in turn, refers to the little-known flip side of the Narcissus myth.

“Most of us are familiar with how Narcissus was obsessed with his reflection in a lake, and he died or drowned or something like that,” Gee says. “Not so well known is that he had this secret admirer named Echo. How ironic! Anyway, Echo was in love with Narcissus, thought he was beautiful. But Echo was already cursed to repeat whatever anybody says. That’s the backstory—she’s already cursed. So she just follows Narcissus around and repeats everything he says. He finds her super-irritating and tells her to bug off; she’s heartbroken, but she doesn’t bug off. She just continues to sit around and repeat everything he says.

“What I find interesting about this is that it’s almost an allegory for the human condition. Narcissus is a human man, and Echo is a golem or a nymph. She’s not a human, not a god: she’s kind of this object-y thing. She’s of nature—but she’s also a woman, and doesn’t have a voice. She is the signal-to-noise relationship.”

Some might find it hard to square Gee’s feminism with her next project: a video game using pop music as weaponry. That as-yet-untitled undertaking, commissioned by Toronto’s Trinity Square Video, will use Gee’s galvanic-response sensors for input; players’ success will depend on how effectively they can animate the game’s digital, anime-style digital pop stars.

“I’m kind of spoofing on the first-person-shooter, military genre of video games,” she notes. “Imagine a military future where drone technology has been perfected; basically fighting has become incredibly easy, yet for some reason human bodies still need to inhabit these things, ’cause it’s a war. The biggest problem is that although things have gotten de-skilled and automatic and whatever, PTSD is rampant. So a bunch of entrepreneurial minds got together and decided that they should revitalize the classic tradition of pop musicians cheering on the troops—and you need to give the ultimate performance. They’ve already written the pop music for you, and you already look hot, ’cause you’re a hologram, but you need to give your emotions, so that people can feel your performance.”

Typically, though, there’s more to the idea than there seems.

“I really hope to make it be so problematic that it raises questions,” Gee says. “There is this militainment industry in video games that does glamourize war, and often the person that you play is some macho army dude. In this case, you are going to be an anime pop star, so it already decreases from the macho fun of typical militainment. You create entertainment by turning on your fake emotions for the war.

“People will respond to this in different ways,” she concedes. “I took it to one expo, just talking about the ideas, where afterwards these very macho guys came up to me and were like ‘Oh my god, your video game sounds sweet. I am so awesome at fake emotions.’ And I was like, ‘Oh, okay.’ But it kind of is what it is. Art is for everyone, for better or for worse.”

And is it better if that art includes an element of subversion?

“I would say so,” Gee says. “But if you don’t see it, maybe that says more about your politics than mine.”

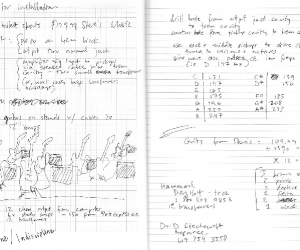

Photo still, top, of Erin Gee's audiovisual work Voice of Echo by: Kotama Bouabane. Biosynth (2016), developed by Erin Gee, for quickly sonifying physiological markers of emotion with simple FM synthesis in hardware. Erin Gee (bottom) circa 2014 by: Nick Hyatt