Suit-tail-clad Juliet Palmer sits at the top of a stepladder in the middle of the diamond-shaped ring. Tonight, she’s not wearing her Canadian composer hat. Tonight, she’s a sports announcer.

“Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, welcome to Voice-Box!” she booms. You can almost imagine her clasping a vintage mike hanging from the ceiling.

Leaning against the ladder is modern dancer Julia Aplin, clad in a referee’s uniform. A hype girl—in the form of playwright Anna Chatterton—sashays around the ring, holding a sign reading “Bout 1.”

In one corner stands Savoy Howe (a.k.a. Savoy Kapow), one of Canada’s foremost female boxers. Kapow’s coach for the evening’s event is mezzo-soprano Vilma Vitols, who operatically sings words of encouragement between rounds. In the other corner, vocal improviser Christine Duncan and soprano Neema Bickersteth create a musical number out of taunting Kapow’s opponent—“Who are you fighting—your sister?”—who is named Ghost Rider, and is a pumpkin.

You read that right. This is Voice-Box, the newest piece by the Toronto collective Urbanvessel, and it begins with a fight between a boxer and a pumpkin. Voice-Box involves music, lyrics, and plenty of dance, but also has a healthy dose of humour, and it may be the only time you see a tango evolve into a boxing match. Voice-Box takes on the world of women’s boxing, exploiting the thrusts, jabs, bobs, and weaves of its movement and the shouts and slams of its sound-world to create a performance piece that smashes the boundaries between disciplines and leaves them sprawled out on the mat, down for the count.

“Interdisciplinary” . . . “site-specific” . . . “non-hierarchical” . . . These are common buzzwords in the modern art-world, usually overstated for the sake of grant applications. But Urbanvessel is a group that actually does the things that others claim to. Over the last four years, this loosely defined group of women artists—who claim to have no official leader or director—has created an increasingly sophisticated series of pieces that seek to empower audiences by informing them about relevant social issues—as well as things the collective is passionate and obsessive about.

Urbanvessel premieres at a public pool

Urbanvessel began with a splash—literally. Their first major piece, Slip, was staged in Harrison Baths, in September 2006. Located on Stephanie Street in Toronto’s Grange neighbourhood, near OCAD University and the Art Gallery of Ontario, the baths are actually a public swimming pool, since renamed Harrison Pool, known locally as a refuge for homeless men, most of whom don’t go there to swim but to shower. The men’s change room, as such, has something of a scummy reputation in the neighbourhood. It was the perfect place, of course, for a group of fearless women to invite a group of strangers to witness a production incorporating sound, movement, projections, and perfectly executed swan dives. Based on the storytelling and oral memory around the pool, Slip was a non-narrative play in which the forty audience members attending each run were led through the pool’s various dimly lit rooms, experiencing both awkward face-to-face encounters with cast members, and absurdist scenes such as drummer Jean Martin reading the newspaper beneath an umbrella in the shower—situations which reveal something of this group’s surreal sense of humour.

The idea for Slip came out of a conversation between Urbanvessel’s co-founders, architect Christie Pearson and composer Juliet Palmer. Palmer is a New Zealand native who moved to New York to intern with vocal-multimedia icon Meredith Monk before settling in Toronto in 1998 to live with her Canadian husband (and fellow composer) James Rolfe. Not feeling immediately at home in the city’s new-music scene, she felt more welcomed by those in dance circles. Yet before getting a music degree, Palmer was studying to be an architect, and kept up an engagement with the discipline. She met Pearson through architect friends, and the two hatched a plan to renovate Palmer’s house. When that plan was deep-sixed by budgetary concerns, they decided to make a piece of art together instead.

Palmer took an interest in Pearson’s obsession with the culture of bathing. “We were intrigued by the ritual of cleansing and the notion of hygiene, which is a very Western notion,” says Palmer. “So we were just jamming with that idea and we decided to make a piece.”

“I made a bathtub out of ice which was installed in front of Harrison Baths—the last of the free Toronto swimming pools,” explains Pearson. “You actually used to be able to have a bath there. I was really interested in the place and I wanted to do something there. Our brains just merged to create this project in a swimming pool.”

Toronto’s cultural coming of age

The timing of Slip is significant—especially for a group whose name contains the word urban. It happened in 2006, a year that marked something of a coming out for Toronto culture. Just a short week later was the very first edition of Toronto’s Nuit Blanche, the “all-night contemporary art thing” which, though imported from Paris via Montreal, signified an unexpected hunger and curiosity in the general public for engagement both with Toronto’s urban environment and with non-traditional arts. The long-overlooked new-music scene, meanwhile, was treated to the launch of two new festivals: New Music Arts Projects’ soundaXis Festival and the Music Gallery’s X Avant Festival.

Urbanvessel took part in both sets of festivities. Slip was co-presented as part of X Avant, yet it was preceded by Four Lines, the first Urbanvessel piece to be publicly presented, at soundaXis in June 2006. That first soundaXis was focused on “music, acoustics, and architecture” and was partly inspired by the frenzy of architectural activity in the cultural sector at that time. 2006 marked the opening of the Canadian Opera Company’s new home at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, as well as the redesigned Gardiner Museum for ceramic art. The ROM’s controversial crystal wing would follow in 2007, while the more beloved AGO re-opened in 2008, and the Royal Conservatory of Music opened the doors to their new digs in 2009.

Four Lines was less concerned with celebrating institutional temples for established traditions, and more about going off the beaten path—literally. Engaging some of the most outstanding members of Toronto’s improvised music community, Four Lines sought to engage free music with public space in the form of a “mobile prelude.” A one-off event conceived by Palmer and Pearson, Four Lines featured four sets of performers moving through downtown Toronto, each from a different starting location, until they converged upon the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research at the University of Toronto, where they performed together throughout the space. Double bassist Rob Clutton began playing behind the AGO in Grange Park, and wheeled his bass northward when taking breaks. Vocalist Christine Duncan and percussionist Jean Martin, who work together as Barnyard Drama, sang and played as they wandered south along U of T’s Philosopher’s Walk. Sarah Peebles and Nilan Perera, meanwhile, mixed ambient sounds from the urban environment as they travelled to the centre via pedicab and TTC subway system, respectively.

Four Lines was very well received, according to Palmer. “It drew people into listening in a different way, and listening to the nooks and crannies of the city. It was also about being in that building, which had just opened. Often people don’t feel like they have permission to just walk around institutional spaces like that, so people like to be let in.”

The warm reception that the SoundaXis Festival received took the Toronto new-music community—accustomed to being ignored by the media and shunned by audiences—by pleasant surprise, as many of the concerts saw packed houses and supportive press. Likewise, the first Nuit Blanche saw crowds of close to half a million wander the megacity’s streets at night, discovering hidden wonders, including penguins in Harrison Pool, illuminated tents in Trinity Bellwoods Park, and Pearson’s own “Night Swim,” an all-night pool party, music festival, sound installation in that park’s nearby community centre. The vibe that night was electric, with regular citizens and artists alike all turned on by this new mode of discovering art.

But the seeds of any movement’s demise can be seen being sowed at its height. That same utopian night of Nuit Blanche ’06 saw an ugly underbelly exposed. Darren O’Donnell’s piece Ballroom Dancing—designed as an innocent social experiment consisting of an all-ages dance party in a gymnasium filled with rubber balls—ended with teenagers turning the whole scene into a near-violent game of murderball. Succeeding editions of Nuit Blanche saw the crowds and rambunctiousness increase, to the point where the sense of joyful discovery was smothered by the unpleasantness of the experience. During the last soundaXis festival, Toca Loca, a Toronto-based new-music ensemble, were offered twenty dollars by a merchant’s personal assistant to stop playing on the corner of Queen and John in Toronto. They accepted. Since then the soundAxis festival has suspended their festival operations for primarily financial reasons. And the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, where Urbanvessel had its première? Its beautiful indoor bamboo forest had to be chopped down due to a plant virus.

Some people asked themselves if the dream, just as it had begun, was over, and whether it was possible for art to really change the fabric of the city. Was it just a delirious one-night stand only self-delusionally of social relevance? Darren O’Donnell, in his long-form essay “Social Acupuncture,” published in, yes, 2006 by Coach House Books (who also published the influential uTOpia book series that documented this cultural moment), questioned his own involvement in the sort of socially engaged art projects that exploded in Toronto circa 2003. “Did I really organize talking parties for strangers and play Spin the Bottle with a room full of adults? How did I end up spending so much time believing that culture had some revolutionary potential? What was I thinking?”

Can art effect social change?

Ask the members of Urbanvessel if they think art can effect social change, and you get a variety of responses.

“Yes, of course!” says dancer-choreographer Yvonne Ng, who worked with Urbanvessel on Slip. “In our diverse community here in Toronto, a deeper understanding of, and a more generous appreciation for, each other’s culture serves as a healthy ground for challenging dialogue and progress.”

Anna Chatterton, however, shakes her head. “I don’t think it’s possible,” says the librettist. “But I like to make people think about things.”

“You can’t separate your beliefs from your art,” says Juliet Palmer. “But you don’t want to make work that’s didactic.”

The only common thread here is reluctance within this group of artists to describe their art as activism. This may be an old story: “art for art’s sake” has been a rallying cry since the early nineteenth century—mainly as a response to societal pressure to produce art that validates mainstream morality. But in the twenty-first century, many artists increasingly feel that art alone is not enough—especially when the media constantly bombards us with bad-news stories, like poverty, climate change, and violence against women. You feel the need to do something—but what? And bringing politics into one’s art still holds a stigma—look at the way rock stars like Bono are mocked when they try to use their celebrity and wealth to further a worthy cause.

Palmer hopes that Urbanvessel’s work can find a middle ground between art and activism—call it social engagement, if you will. Shortly after they remounted their second major production, the Dora Award-nominated Stitch, I sat down with Palmer and Christine Duncan to discuss their work, meeting up with them at the Holy Oak Café in Toronto’s Bloor and Lansdowne neighbourhood, an area that is home to several newcomer communities and some of the west end’s worst poverty, but whose character is slowly being changed by a gradual influx of artists and art spaces such as Mercer Union and Toronto Free Gallery.

“It’s about entering into an unfamiliar space and having your perspective altered,” says the composer. “You experience your relationships and the city differently. We did a very simple exercise when we were doing Stitch, where we got people in a circle to check their neighbour’s shirt and find out where it was made”—Palmer stops and pulls out my T-shirt tag: El Salvador!—“and then went around the circle and accumulated place names. And even doing something that simple, you find out that many people have never actually considered that. It’s not like I’m saying, ‘stop buying those evil sweatshop shirts!’ But it still makes you think, ‘well, who was that person in El Salvador who made my shirt?’ It alters your relationship to the world.”

True to the collective’s aims to engage with the urban environment and take the audience into unusual, unfamiliar, and sometimes uncomfortable spaces, Stitch was originally mounted in 2008 in Toronto’s Lennox Contemporary gallery, the site of a former sweatshop. A non-narrative, a cappella opera, Stitch featured just three singers (Christine Duncan, Neema Bickersteth, and Patricia O’Callaghan) and three sewing machines sitting in the middle of a darkened room; yet, as John Terauds of the Toronto Star wrote, “it crosses so many genres as to be in a category of its own.” Stitch used minimalist, repetitive chants and the percussive trundle of the sewing machines to hammer home the dehumanizing nature of the garment industry, but made the topic approachable through bursts of song and humour that expressed the characters’ fears, desires, resentments, and dreams.

“Stitch definitely connects to the history of Toronto and its place in the global economy,” says Palmer. “There’s a mythological dimension to it and there’s a socio-political dimension to it. To me, there are two worlds in that piece. One is a more lyrical world that’s pre-industrial, and the other reflects a loss of that holistic view. We’re clothing ourselves through an industrial process that fragments the construction of our personal architecture. And that fragmentation happens in terms of our connections to each other.”

It is perhaps a desire to overcome this sense of fragmentation and to forge vibrant connections with her community that has led Palmer to create such an egalitarian collective of artists. Though she is “the sun around which we all revolve,” according to Duncan, and the one consistent member of the creative team on each Urbanvessel project, Palmer is eager to share credit and allow her collaborators to participate in every level of creation. But there is a certain chemistry that Palmer looks for when it comes to choosing her collaborators.

Duncan says, addressing Palmer, “You’re very specific in terms of who you want to work with, and you do your homework in terms of the perspective that each one of the artists has, and what they’re open to.”

“Yeah, we have to inspire each other, and be flexible,” says Palmer. “We can’t have any prima donnas, or people who are too rigid or stuck, in this kind of environment.”

One thing that sets Urbanvessel apart is the way in which the lines between roles and disciplines are blurred. But this isn’t done to make some kind of political point; it’s more for the sake of camaraderie, and sometimes, just getting the job done, in an old-fashioned barn-raising style.

“We’re working together to build something and we figure out whatever that project needs,” says Duncan. “These guys [the creative team] end up performing half the time. So it’s just a matter of working with people who are open and flexible to doing whatever it takes to make the piece happen. It’s not so premeditated—like, ‘Now we’re going to get the singers to dance.’ It’s never like that. It’s more like, ‘You know what this piece needs? We need a little dancing in this piece. Let’s all try to dance.’”

Next bout, tango!

All the members of Urbanvessel get a chance to bust out some moves in the collective’s newest production, Voice-Box. Premiered November 2010 in Toronto at Harbourfront Centre’s World Stage, Voice-Box is a full-on face-off between a cappella music and physical movement, set in the world of women’s boxing. Banned worldwide for most of the twentieth century, women’s boxing only emerged in the 1990s, and still suffers from low visibility and stereotypes about it being an inappropriate activity for females.

Voice-Box is not just inspired by women’s boxing; it features real boxing—and a real boxer: Canadian women’s boxing champ Savoy Howe. Founder of Toronto Newsgirls Boxing Club in 1996, Howe is a pioneer in the field, but also has a background in theatre and stand-up comedy, and thus fits in perfectly among the cast. Yet it was another cast member picking up the gloves for the first time that led to the birth of Voice-Box. Around the same time that Slip premiered, mezzo Vilma Vitols took up boxing.

“I was having nightmares in which I was pummeling my ex-boyfriend and always had to escape,” explains the statuesque Vitols. “So I needed to go somewhere where I could hit things.”

Their friend’s new activity intrigued the rest of the Urbanvessel crew enough to create a new piece that, like Stitch, is a non-narrative opera of sorts, and is presented like a boxing match, with a series of “bouts” that incorporate voice and dance elements. In one scene, Savoy can be seen battling her inner demons, led by Duncan shrieking like an ominous bird of prey; in the next, she is being celebrated in a ’50s-style musical number that recounts the history and heroines of women’s boxing—the “educational” section, as Palmer describes it.

Palmer’s music for Voice-Box takes on pop forms in a way her chamber work, such as the Alanis-inspired Five (Hand in My Pocket), has so far only hinted at. Neema Bickersteth undertakes a solo dance to a minimal techno piece that eventually involves the whole company, including the writer and composer. Modern dancer and choreographer Julia Aplin also dances solo—while covered in blood—to Palmer’s first piece of Swedish death metal. She found composing this piece to be a unique challenge, not in rendering the music’s rhythmic virtuosity—the link between classical and heavy metal in general has been pointed out by many a music critic—but in capturing the visceral quality of the music’s sound.

During one bout, Duncan and Vitols take on an operatic, atonal voice-off, which ends with Duncan pinning her opponent to the mat using just her vocal cords. It is this expression of the physical power of sound that makes Voice-Box such a strong piece. It’s also a celebration of women’s empowerment within fields that, until recently, were the domain of men only—not just boxing, but composing as well.

Palmer plans to explore feminist themes further in her next piece, an as-yet-untitled collaboration planned for 2011 that is based in actor Margaret Lancaster’s experience of being stalked.

“I care about things!” exclaims Palmer, when asked if this is another example of art as social engagement. “Sometimes I will go to a concert of ‘pure’ chamber music and I think, this is the weirdest, most obscure art form—it can feel like it’s in a bubble. I don’t want to feel so disconnected from the world and from people.”

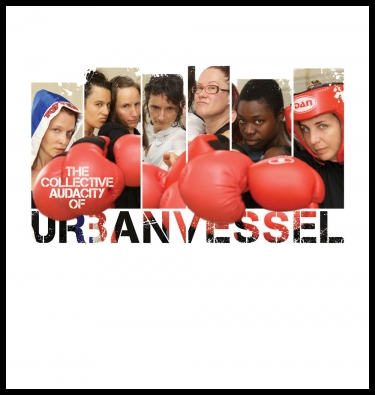

Audio: Slip—Simple Death (Excerpt, 2006). Composed by Juliet Palmer. Performed by Christine Duncan and Aki Takahashi, voices. Lyrics by Anna Chatterton. Image: Members of Urbanvessel get ready to rumble in their performance of Voice Box. Image by: Adam Coish. Image designed by: Lucinda Wallace.