On a summer evening, outside this art gallery-cum-coffeehouse somewhere on the Gulf Islands, silver-green alders, not yet dry and summer-drab, sway, as deer graze in a meadow beyond, and small birds sing. Inside, a young couple performs. Julia Ulehla has spurned the venue’s microphone and is keening deep into the timber-framed space with a voice that’s both wild and consummately controlled. One minute she’s crying down a mountainside, the next shooting for the back rows at La Scala, her early operatic training shining forth.

At one point she kneels, her eloquent hands carving air in front of her face. It’s not an act, like the late Leonard Cohen’s practised obeisance, but an honest response to tragedy; in this song, “Na stráznickém rynku,” a young man has been conscripted for battle, and his face is already pale with imagined horrors. She is both the stricken boy and his forlorn lover, and it’s not so much acting as embodiment.

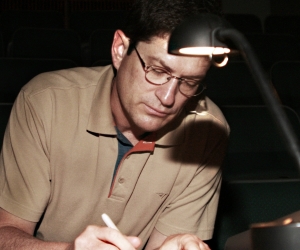

Meanwhile, her partner Aram Bajakian is hunched over an electrified acoustic guitar. The casual listener might mistake what he’s playing for some distant relative of gypsy jazz. To match Ulehla’s singing, he plucks spare minor chords and suggests the oom-pah basslines of a Middle European harvest fair. But inside that almost-familiar framework there’s more. Sprays of silvery harmonics emerge when he digs into his bass strings with the edge of a pick. Eccentric, superimposed rhythms are fingerpicked with classical precision. At one point, he steps on an effects pedal—built, he says later, for his mentor Lou Reed—and a terrifying roar fills the house.

The void briefly opens up and nearly swallows singer, guitarist, and audience in a wave of fear that ultimately turns to a rush of wonder.

At the end of Ulehla and Bajakian’s performance, there’s a pause. The listeners—a small but attentive crowd of mostly artists, poets, and musicians, but also retirees and recycling-depot workers—do not want to let the moment go. And then they rise in a standing ovation.

Ulehla and Bajakian call their duo Dálava. That’s also the name of their band, which on its brilliant sophomore recording, The Book of Transfigurations, also includes Vancouver improvisers Peggy Lee on cello, Tyson Naylor on keyboards and accordion, Colin Cowan on acoustic and electric bass, and Dylan van der Schyff on drums. Both the duo and the band create twenty-first-century settings for songs from Moravia, once an independent state but now a province of the Czech Republic.

The region, as Ulehla describes it, sounds like a place out of time. In her grandmother’s village, it’s not uncommon for a friend to drop by with a rabbit for the stewing pot, the neighbourhood dress code is decidedly relaxed, and the wine flows like water. Or so she and Bajakian discovered last summer when they took their duo to the land that inspired it.

“You know, the man comes to help fix the car, and he’s wearing his underwear,” reports Ulehla . “And it’s not highfalutin’ wine country, but everyone makes wine . . . While we were there, this very kind man invited us to visit his little patch of land where he grows grapes and makes wine. He took us on a tour of these achingly, stunningly beautiful hills and vineyards, and I had this—all I can say is, some kind of shock, where I felt confronted by the place. It was some kind of existential crisis or epiphany that I felt in my whole body”

Yet even before that experience, the land was present in every note Ulehla sang.

Her great-grandfather also believed that geography shapes culture, and so shapes song. A contemporary of Hungarian composer and folk-song collector Béla Bartok, Vladimir Úlehla was a biologist whose passion for ethnomusicology led him to research and write the definitive treatise on Moravian song, Živá píseň (Living song). Obsessively annotated and meticulously transcribed—Vladimir even built a seismograph-like device to measure the length of his rural singers’ vocal phrases—this 1949 publication is Dálava’s grail, sourcebook, and spirit guide.

“My great-grandfather likened [traditional music] to an organism, in that it had an ecological place that it came from; it could be born, it could stay alive, and it could die,” Ulehla explains.

If there’s no incongruity in Dálava’s blend of ancient song and modern instrumentation, that’s in large part due to Bajakian’s extreme sensitivity to what a singer needs in order to thrive—a gift he’s previously exploited in his work with Reed and Diana Krall. Although the guitarist was the one who first pushed the idea of working with Vladimir Úlehla’s folk-song transcriptions, Dálava was likely inevitable—and it’s just one aspect of an almost lifelong friendship that has blossomed into romance, collaboration, and the creation of a family that now includes two young daughters.

“I feel the need to tell you that Aram and I met when we were about fifteen,” Ulehla confides. “I was already singing mostly more classical stuff and Aram was already playing guitar. And I remember that Aram, even then, always had this super-strong creative force that was obvious and clear.

“We went our separate ways in our twenties, but we kept in touch,” she continues. “And then I was living in Italy, working as an actress, and Aram was on tour, and we came together. When we started collaborating, there was already this sense of—I don’t know—not awe, but space. It was like we could give each other space to conjure what we each needed to conjure.

“When we create together there’s a process that sort of happens where I will sort of sequester myself with the song for a long time, and just see what it does to me, and see what the terrain seems to be. Sometimes there’s almost like a fire, or something, and sometimes it’s very spacious and vast—all these different kinds of impressions or densities or colours that the songs bring up. And then, once I feel like that is strong enough, I bring it to Aram and we find our musical way together.”

In concert, in either band or duo format, Bajakian and Ulehla create a sound that is achingly intimate. Their love for the music and for each other is beautifully evident, and not in any kind of saccharine fashion: it’s as if they share a mutual incandescence. And there’s another aspect of their project that they share: as the children of immigrants, both are trying to locate themselves in this new world and—since their 2013 move from New York to Vancouver—in a new city and country as well.

Ulehla, at least, has her great-grandfather’s book to link her to the European past; it’s also the focus of her Ph.D. thesis in ethnomusicology, which she’s pursuing under the direction of gamelan specialist Michael Tenzer at the University of British Columbia. In contrast, Bajakian’s ancestral home was likely razed or expropriated during the Armenian genocide that took place during the early part of the twentieth century. And, being a guitarist and an American, his early roots were in rock, noise music, and free improvisation.

“As a person who doesn’t speak Armenian, I always felt kind of like an outsider within the Armenia club,” he says wryly. And while Ulehla ’s doctoral studies touch directly on her heritage, his master’s in composition, with an emphasis on electronic music, doesn’t. Still, he’s increasingly drawn to Armenian themes, even if he tends to discover them by chance. That, at any rate, was how he discovered Sergei Parajanov’s film The Colour of Pomegranates, which he’d go on to translate into sound on his 2015 album Music Inspired by The Colour of Pomegranates.

“I’m in New York,” he recalls, “staying at my friend Shamir Blumenkranz’ place, and his Japanese wife says, ‘Oh, Aram, you should see this film. It’s by an Armenian director.’ I’d never heard of this guy—but, literally, I was there for two hours and I couldn’t speak; every scene was such a beautiful image.

“I could relate to so much of it,” he adds. “Seeing a pomegranate get cut at the beginning of the film, I remembered seeing my dad eating pomegranates and my grandfather eating pomegranates, and I realized, that was important to me. It roots me, in a way.”

Nonetheless, he stresses that while he finds the sound of Armenian music inspiring—using an ebow on an acoustic guitar, for instance, can conjure up the sound of the oboe-like duduk—he doesn’t think he plays Armenian music. Ulehla begs to differ.

“I actually feel that you’re really drawn to Armenian things,” she says teasingly.

“Well, I am reading a book about [nineteenth-century monk and mystical composer] Komitas right now,” he replies.

Neither would deny that knowing where they come from is a boon to the production of art. “I feel like it’s essential, in some way,” Ulehla observes. “The further I go with this, the more I realize what a source it is. It brings so much meaning and—I don’t know—richness to the work. And it’s relevant, somehow—relevant to modern life.”

Photo: Aram Majakian (guitar) and Julia Ulehla (standing) of Dálava, behind them Dylan van der Schyff (percussion). Photo by Jan Gates.

Audio: Ej, na tej skale vysokej [Seven pairs of eagles]. Traditional, arranged by Dálava.