Maria De Alvear is a consistently intriguing composer whose World Edition label also releases recordings of music by unique composers of concert music—most recently, Berlin-based Canadians Marc Sabat and Chiyoko Szlavnics.

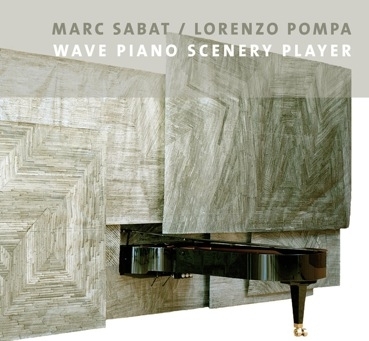

While Sabat is perhaps best known for his interpretations of works by Morton Feldman, Barbara Monk Feldman, John Cage, and notable Canadians like Linda Catlin Smith, he has also produced a diverse catalogue of his own compositions. Wave Piano Scenery Player is arguably the most difficult of these to present on a recording. Initially performed at the 2007 Donaueschingen Festival, the eighteen-hour performance-installation features Lorenzo Pompa’s richly patterned sculptural wall, from which a grand piano (save for it keyboard) protrudes seamlessly. Despite the enormous temporal obstacle presented by the piece, the condensed result makes for quite a satisfying album.

The disc opens with WAKE for JIM, a piece for computer-controlled piano, which rapidly evolves from tolling notes in the low register into an imposingly dense storm of sound. It then thins out to some isolated notes at the other end of the keyboard, the texture again swells into a swarm of activity, this time with more audible punctuation. The mechanized feats of pianistic virtuosity cannot but bring to mind the works of Conlon Nancarrow. Yet a most crucial difference is hinted at by Pompa’s sculptural obfuscation of the performer (or lack thereof). Through its granular approach, Sabat’s music manages to produce a strange parallel mirage: as you listen to the ever-growing density, the piano sound seems to dissolve temporarily, an impression sustained until the end of the work.

To Damascus also stages hallucinatory extensions of the piano’s sound through the conjunction of the instrument and technology. A concert work also designed to be performed from behind Pompa’s sculptural environment, it features live piano (played here by Sabat's frequent collaborator Stephen Clarke) whose upper partials are gently teased with sine tones that thread through each sonority. Here, the relationship between electronics and instrument remains fixed, akin to a piano with movable preparations inside of it.

The music on To Damascus and on the recording’s shorter pieces reveals a surface of both stasis and endless diversity. Clusters of activity—piano gestures of varying density and weight—present themselves in succession. Each unique moment initially makes it difficult to determine relationships between the segments of material. However, as the listener becomes more immersed in the activity of listening, the cryptic linearity of events is no longer a concern. Instead, each event deposits itself into a larger evolving image, where each fragmentary sonority is clearly related, as the various overtones resonate in our ears. Sabat and Clarke, who produced a noted recording of Morton Feldman’s For John Cage, are intimately familiar with the manipulation of perceived time and memory, and this is in clear evidence here.

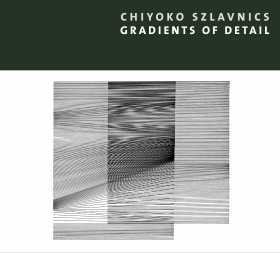

The three diverse works on Chiyoko Szlavnic’s Gradients of Detail are mostly in contrast to the peculiar, discrete sonorities on Sabat’s disc, yet they also articulate fluctuations in tone colour. The album artwork consists of Szlavnics’ own line drawings, which exude a stringent purity of execution, while animating a world of complex intersections. Not surprisingly, there is a strong connection between her music and the concerns of her visual work.

Both (a)long lines: we'll draw our own lines (expertly rendered by Ensemble musikFabrik) and the title work (played by the Asasello String Quartet) work a great deal with the microsonic collisions of glissandi and smooth pure tones. The music is sustained yet in constant motion, and manifests itself in distinct, albeit extended, gestures, rather than a single undifferentiated field of sound. Many times these long moments of dynamic suspension are ignited with brief colourful punctuations. While this music is stylistically dissimilar to Feldman, it tends to bring that composer to mind, if only to note that each of these sound panels exhibits an extraordinary sense of orchestration and temporal placement. Similarly, their juxtaposition offers an elegant, mysterious, and entirely individual take on slow-motion lyricism.

The brief second piece, Her Teeth Were White, provides a breather between the two longer, comparatively denser tracks. The nearest point of comparison here is to the newer work of its dedicatee, Christian Wolff, in its openness, economy of material, and odd tunefulness. Each succinct phrase carries a supple pulse, but also a gravity toward cadential resting points; percussionist Dirk Rothbrust’s varied palette of soft and round sound follows these shapes with an understated temporal elasticity and subtle dynamic range.

It might not be entirely accurate to characterize such nuanced and frequently delicate sound as bold, yet there is nonetheless a solidity to even the most fine and abstruse textures as they stretch through time. Similarly for all its clarity, you’d never want to label this work austere, as its covert celebration of the inner life of sounds conveys a tangible warmth to the listener.

Both Wave Piano Scenery Player and Gradients of Details are powerful contributions to the World Edition catalogue, reinforcing its growing reputation as an eclectic repository of inventive and beautiful music.