Walking away from the Thames on the final night of the London Contemporary Music Festival (LCMF), I was reminded of the classic scene from The Simpsons in which Bart’s friend Nelson emerges from a screening of David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch and says, “I can think of at least two things wrong with that title.”

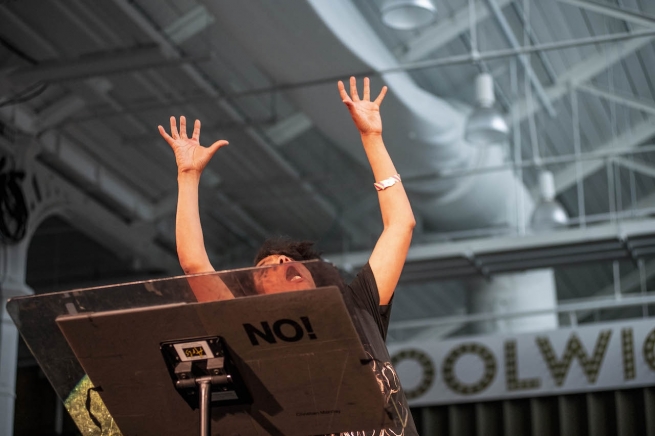

If the LCMF is considered a music festival, that’s only for lack of a better term. The first night was given over entirely to a performance of the touch-heavy interactive dance piece Inchoate Buzz (London having lifted most COVID-19 restrictions); other nights had quite as much dance, poetry (confessional, conceptual, or sound), experimental film, and video art as music. Music seemed selected as much for its theatrical effect as its musical one. Unfolding in a long, large room at Woolwich Works in southeast London, performances and screenings rotated between three stages around the outside of the space and a clearing in the middle of the audience, with performances occasionally moving right into the sea of backless benches. There were no introductions or banter either: literary or theory-heavy program notes were the only indication of what was happening at any given moment.

The festival’s theme, “The Big Sad,” was similarly (happily!) misleading. Each day’s program had a thematic description that moved between two emotions (“Sad and Ruined,” “Ruined and Exhausted,” “Exhausted and Hysterical,” and finally, “Hysterical and Happy”), outlining a sort of emotional journey. Throughout the festival there seemed to be an inability or unwillingness to maintain a coherent emotional landscape, even through a single piece of music, much less through an entire program. Sometimes this inconsistency was due to forces outside of the organizer’s or artists’ control. Several pieces (Clara Iannotta’s Eclipse Plumage, Rebecca Saunders’ dust II) were so quiet that the sound of an errant wine glass hitting the floor or the door brushing open and closed was a substantial distraction. Ewa Justka tried in vain to interrupt her entertaining set of frenetic techno-via-homemade electronics to complain to the technicians that the performance was supposed to take place in total darkness, not blazing theatrical lighting. But overall the festival was a technical tour-de-force. My experience of the last piece, in which trumpeters on three boats on the Thames played the same note at regular intervals as they drifted further and further apart, was interrupted persistently by a singularly miffed audience member who couldn’t seem to stop herself breaking the long and otherwise meditative silences to tell her companion that “everything after Joëlle [Léandre] was a bit off” and snickering at the (admittedly patience-testing) festival send-off.

Most of the time, the emotional incoherence was intrinsic to the programming itself, either within a given piece or between pieces, through jarring but clearly considered juxtaposition. Perhaps the highlight of the festival was a performance of Christian Marclay’s No! by unconventional vocalist Elaine Mitchener, which began with a long silence followed by a sudden loud gasp that took the whole audience aback, and which climaxed with a series of variations on the word no—dramatic (“No.”), comic (“nuh uuuh”), screamed (“NOOO!!!!), muttered (“no…”), and so on. Jerskin Fendrix’s Winterreise, too, dwelled in undecidable emotional territory: Schubert references sitting side-by-side with histrionic millennial crooning, video-game electronics, and operatic (or Phantom of the Opera) theatricality, Fendrix perched at a grand piano in the middle of the audience, surrounded by synths, convincing you to take it seriously while daring you to laugh. At other times, the programming seemed deliberately engineered to disorient; the last acts leading up to the Thames excursion were a classic free-improvisation bass solo by Joëlle Léandre, a gorgeous bit of Gaelic choral music from Musarc with the incongruous title Sippy-cup without juice, and the chaotic electronics of Ewa Justka.

The festival leaned heavily on the sad-boy aesthetics of Alex Mazey, who was quoted extensively in the program notes alongside a who’s who of continental philosophy and poststructuralism—Baudrillard, Freud—and who was featured at the festival’s panel discussion (which I did not attend). An appearance by the sui generis but Internet-y rap-adjacent artist Triad God, whose confessions and electronic meditations—that mix of vulnerability and artifice—was probably the best approximation of sad-boy aesthetics. Appearance is a generous term; in fact, he performed behind a screen showing a picture of him and snuck off at the end of the set without most of the audience noticing. More artifice than vulnerability, when push comes to shove, I suppose.

I have reservations about the festival’s deriving inspiration not from the music but from such extrinsic themes. The LCMF demanded not only a conceptual bent, but also an openness to a dizzying range of musical genres, artistic mediums, and presentation styles, all of it presented rapidly and without further comment. To remark that the festival was uneven, that some performances were better than others, is to miss the point—unevenness was the point. All fun as far as it goes, but possibly a tough sell to non-initiates; without that sort of depressive Dadaist sensibility, your mileage may vary.

PHOTOS BY DAWID LASKOWSKI

Top: Eve Stainton performs in Fernanda Muñoz-Newsome's Inchoate Buzz

Middle: Elaine Mitchener performs Christian Marclay's No!

Bottom: Joëlle Léandre