Last Christmas, our new Syrian friends were telling us about dabke, the Syrian line dance. “Dabke,” I said. “That’s what Omar Souleyman plays!” They laughed out loud and said, “We’d never heard of him in Syria, but now that we’re here, he’s all anybody talks about. His music is so silly!”

Omar Souleyman is a celebrated artist in North America and Europe, and that stardom largely comes courtesy of Sublime Frequencies. Cofounded by Alan Bishop, of the cult avant-rock band Sun City Girls, and music archivist and filmmaker Hisham Mayet, Sublime Frequencies is a Seattle-based label specializing in what has come to be called, at least in academic circles, World Music 2.0. Eschewing both dominant modes of foreign music consumption in the West—conventional ethnography from the likes of Smithsonian Folkways and worldbeat crossover hits like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan or Paul Simon’s Graceland—World Music 2.0, the argument goes, packages sounds from around the world under a punk aesthetic, fetishizing the supposed authenticity of various non-Western musics even as it rips them from their original contexts.

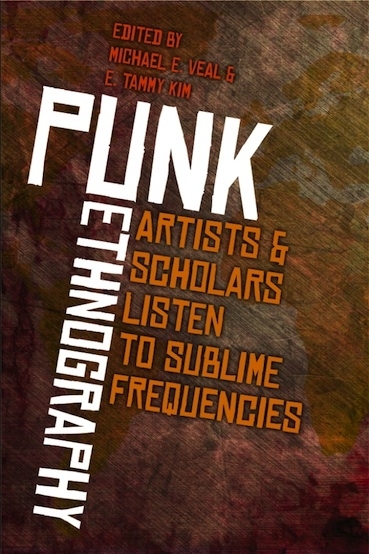

Punk Ethnography: Artists & Scholars Listen to Sublime Frequencies, a new edited volume about the label, is a slightly absurd undertaking, but fascinating nonetheless. Although Sublime Frequencies is reasonably well known in some circles, it is a decidedly niche interest; the 400-page book proudly trumpets the fact of its production without the participation of the people in charge of the label—surely a rarity—and thus seems a gargantuan undertaking.

Most of the essays rest on similar characterizations of Sublime Frequencies releases as World Music 2.0, identifying as problematic their lack of accompanying information and the unsubstantiated allegations that the label doesn’t always pay artists when it can, before attempting to rectify (“demystify”) these issues through original research and analysis. Six pieces take on entries in the label’s collage series—Bush Taxi Mali, Radio Palestine, Radio India, Radio Java, Radio Pyongyang, and Latinamericarpet—in truly herculean efforts that identify and interpret each record’s every uncited sample—some of which last as little as one second—in aesthetic, historical and geographical terms. (The article on Radio Palestine includes a chart that exhaustively categorizes each sample under “Narration,” “Folk,” “Ensemble,” “News,” and other headings.)

Though Punk Ethnography criticizes Sublime Frequencies’ crate-digger stance as exoticist, I think the issue is more complex. Is it really more ethical to imagine we have some knowledge of a foreign music’s context of creation and reception, even if it is irreducibly alien to the one we are in, than to accept its difference and appreciate it on those terms? Omar Souleyman is quoted in the book, saying that he just wants people to dance.

Further, the book’s extensive excavation of the label’s punk genealogy, which it traces back to Sun City Girls’ early days opening for Black Flag, successfully identifies one aspect of the label’s character, manifested in its “raw” aesthetic and its founders’ attitudes in liner notes and interviews. But it elides an equally significant part. It is not until the second-last essay in the book that psychedelia gets a mention—odd, given the blatant exoticism of its titles and cover art, its ubiquitous references to magic, ecstasy, dreams, souls, ceremonies, religions, and cults, and the ensuing talismanic quality of its releases. Just as it is impossible to reduce Sun City Girls to punk aesthetics, as the book is wont to do, to call Sublime Frequencies “punk ethnography” misses an essential component of both its goals and its reception. The label’s exoticism has little to do with the imperialist and academic stenches that adhere to ethnography, falling closer to the tradition of Orientalist spirituality of, say, Brian Jones’ “discovery” of the Master Musicians of Joujouka, or the dialogue between avant-jazz and African and Indian musics.

Though Sublime Frequencies is as psychedelic as it is punk, Punk Ethnography is correct to identify the label’s uniform branding as an issue. To take the label’s word for it, each of its releases, regardless of its original context of creation or reception, is a quasi-cosmic, visionary, and uniquely danceable undertaking uncorrupted by the norms and strictures of Western capitalist cultural product. The label doesn’t reproduce colonialist fantasy so much as it sidesteps questions of power in appealing to a global punk-hippie aesthetic that prizes affect, sensation, and energy over more detached forms of appreciation. Punk Ethnography’s program of demystification is interesting insofar as it excavates contexts and histories that Sublime Frequencies is content to gloss, but its critique is misplaced; it ends up providing precisely the service that founders Bishop and Mayet identify as a justification for the label’s aesthetic and curatorial strategy. The information is out there, and you can find it if you’re interested; Sublime Frequencies is just about the music.