“Rules in cooking are not iron-cast (and, as in any medium of expression, they are often bent or broken by practitioners of talent—but to break rules, one must have rules). They are merely the expression of a well of experience formed and enriched over the centuries, re-examined, modified, or altered in terms of changing needs, habits, and tastes.”

—Richard Olney, Simple French Food

Analogies between cooking and writing music flow easily from composer Nico Muhly’s lips. “There was a certain point in the presentation of food where you would have eggs Benedict, with the idea of a foam of bacon over here and over there a single chive,” he observes. “I like the fun in that, but at the end of the day I’m still interested in the classic French procession of dishes, be it three courses or nine.” Muhly—a self-taught chef and gourmand—can enjoy the presentational disjunctions of molecular cuisine, but he recognizes that they belong to a specific cultural moment. Comparably, he loves the “insanely non-narrative” organization of Philip Glass and Robert Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach, but that work too is of its time and Muhly’s own taste is for the return of a more traditional kind of narrative clarity and coherence.

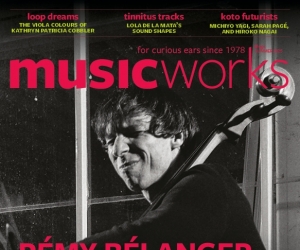

We are talking at London’s Coliseum, home of English National Opera and the venue for Two Boys, Muhly’s first full-fledged operatic venture. Solidly built yet still boyish in appearance, dressed with studied informality in black jeans and T-shirt, the thirty-year-old New Yorker seems comfortable in the wood-panelled Edwardian surroundings, and at home in the process of joining classical music’s equivalent to the long tradition of cuisine classique.

Caught up recently in a media feeding frenzy, Muhly doesn’t initially seem to relish the prospect of yet another interview. But conversation is another matter, and his demeanour soon shifts from polite attentiveness to animated engagement and refreshing candour. I casually mention the late Ronald Johnson, a Kansas-born poet and cookery writer who, like Muhly, took an English degree at Columbia. The name is unfamiliar and gets entered into Muhly’s well-thumbed notebook. This is a small but illuminating sign of Muhly’s receptive alertness, seizing on a lead to follow, a potential source of something to savour.

As Muhly talks with surges of exhilaration you can imagine flashing synapses as he gives voice to an enthusiasm or expounds a point of view. You soon become aware of his dedication to those kinds of creative pleasure that spark an interplay of senses and intellect, but it’s equally clear that his energetic self-confidence is grounded in a deep respect for craftsmanship. He has no time for that threadbare romantic conception of the artist as lawless outsider, or the hollow pretence that originality materializes out of thin air. Creative work, bluntly put, requires discipline, know-how, and rules that may be bent or broken by a talented practitioner.

“Writing a classic string arrangement for a pop song is like tailoring a suit,” observes Muhly, who has enjoyed pop collaborations with the likes of Björk, Will Oldham, Antony Hegarty, and Jónsi of Sigur Rós. “It’s a really specific skill that requires knowing A, B, and C before you can do something crazy and cool. It’s a skill that requires knowledge of voice leading, old-fashioned counterpoint, and how to realize figured bass, knowing how to render out a chord cycle, quickly and artfully. That stuff is hard to do, in the same way that deboning a chicken is hard. But the more you do it the better you are at it.”

Muhly received a Master of Music degree from The Juilliard School in 2004. He is aware that he now draws daily on fundamental musical principles and practices learned during that period of formal education. “Juilliard has retained this old-fashioned French system of ear training that comes from Nadia Boulanger,” he explains. “That’s where you learn how to take a chord apart and how to construct a chord, and it’s where you get to understand very advanced late-nineteenth-century functional harmony. There was a theory teacher who made us resolve the Tristan chord into all possible keys. That shit’s useful . . . just learning that there are pathways and little tricks. I actually liked all that old stuff and I was pretty good at it.”

Equally useful in other ways was the experience of working for Philip Glass, himself a student of Boulanger. They are now good friends and freely discuss musical issues, but the early years of their association were less informal, more routine. “It was a job,” Muhly affirms. “I recently conducted his Violin Concerto in Finland, but in those days I was there to work, not to learn from him. Philip was there to work too. He employs people and they have to be paid, so he writes every day, longhand. I would be given a piece of manuscript from a film score, play it into the computer and synch it with the film. Philip is the most disciplined craftsman. I took away that work ethic.” Muhly noticed that if Glass found one of his pieces wasn’t working he would simply sit down and change it, rewriting without fuss. That composure and quiet pragmatism has had a lasting impact on his own approach, not least in the writing of scores for such films as Steve Barron’s Choking Man, Stephen Daldry’s The Reader and Kenneth Lonergan’s Margaret.

Although it would be misleading to categorize Muhly narrowly as an heir to minimalism, certain techniques and procedures favoured by Glass and Steve Reich have left an audible mark upon his compositions. He grew up hearing their work, and it spoke to him directly. “I received their early music without reading anything about it,” he recalls. “So I found it enormously emotional. I’ve never bought the line that a piece such as Glass’s Music in 12 Parts isn’t expressive.” Darting across the room to the keyboard of an upright piano Muhly illustrates his point with a brief excerpt from that long work. It’s music that so closely resembles a theoretical exercise, yet as he plays, standing with head tilted back, he’s clearly transported by its evident beauty.

The cover of Mothertongue, Muhly’s second CD released on the Icelandic label Bedroom Community, is a close-up image of a mouth, lips apart, poised to speak, sing, eat, drink, taste, kiss. I suggest to him that this image is neatly emblematic of an aesthetic embodied in his own music, at once functional, communicative, expressive, and sensual. I pursue the conceit, pointing to the mouth implied in the title of his first CD, Speaks Volumes, and the third, I Drink the Air Before Me. He acknowledges that the mouth image fits his passion for food and for language, his tendency to think aloud, and his practice of keeping a blog that is purposefully conversational and pleasurably chatty.

And he confirms that his training as a boy chorister in Providence, Rhode Island established an enduring love of the singing voice. Amongst the many highlights of Mothertongue are Muhly’s settings for sensitive vocal performances by indie artists Helgi Hrafn Jónsson and Sam Amidon. Here the voice sounds intimate and personal yet physiologically and conceptually connected to innumerable other human voices, as it relays words and stories drawn in from the greater world back out to that world beyond the individual body.

Muhly has retained from his boyhood devotion to English renaissance choral music. He recognizes that the experience of carrying a vocal line within that rich, intricate, and historically laden context enabled him to develop a very particular way of orienting himself within music and, he suggests, within life more generally. “The goal of my music,” he acknowledges, “is an interplay between it being functional—music for use—and a kind of Eros, a sense of the tactile. It’s a hard balance to strike. I’ve found it relatively straightforward to achieve on my own recordings, but it’s more complicated to get that across through other people’s hands and mouths. On the page, in my scores, it isn’t immediately clear how much workmanlike know-how is called for, how much expressiveness and sensuality.”

That interpretive ambivalence became especially apparent to Muhly when he witnessed the young, London-based Aurora Orchestra recording Seeing Is Believing. This recently issued CD includes Muhly’s own compositions, including a concerto written for Thomas Gould’s six-string electric violin, but there are also his arrangements of pieces by William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons. “It’s really Aurora’s disc,” he reflects. “They’ve claimed ownership, and that’s great. People will make decisions based upon the logic that a piece suggests. It’s sometimes the opposite of what I would say, but that’s fine: I don’t like to feel that I’m micromanaging. Composers are the last people you should ask about what their music is doing. Stravinsky, in the middle of his life, said unbelievably stupid things about his own music, trying to make neoclassicism into an intellectual exercise. The composer as intellectual had nothing to do with how that music sounds. A lot of the performance decisions people have to make are about technical things, like vibrato. Aurora played my arrangement of Byrd as they would play Brahms—not what I envisaged at all, but a great decision. You can actually learn so much about your own music when you let go.”

Another recently released CD, A Good Understanding (the title taken from “Psalm 111”), celebrates Muhly’s love for Anglican choral tradition, through music that seeks to capture and relay his own delight and sense of rapture. It was composed initially for the choir of Clare College, Cambridge, but on this recording the interpretation is by the Los Angeles Chorale under the direction of Grant Gershon. Muhly talks of Meredith Monk, a composer of contemporary vocal music he greatly admires, but her work has remained very closely bound to her own ensemble’s performance of it and he views that as a kind of limitation. “I love her sense of static harmony, this flat surface with a kind of insect dancing on top of it. Then with works like Atlas she got to harness the voice for dramatic purposes and more narrative things. I love it so much, but I don’t really take much from it, mainly because her taste for fragmentation and abstract stylized gestures belongs to an era that I’m the child of, but not part of. I like more traditional storytelling.”

As an undergraduate at Columbia, Muhly wrote his major paper on Dickens. “Not at all fashionable,” he concedes, “but there’s craft in his work, and heart, and all these different things in play constantly. I never had the taste for Modernism beyond Virginia Woolf, and always felt alienated from James Joyce even though composers are meant to feel really excited about him. Studying English in the American system involves constant reading . . . which is how I am anyway . . . and at Columbia you find yourself taking courses you wouldn’t necessarily want to take. You find yourself asking, ‘Why am I in a class on anti-colonial resistance in northern India in the 1850s?’ I found that great! You gain access to these enormous discursive envelopes, and for me there’s nothing more pleasurable than reading something that feels as if it belongs to a larger universe. It makes you feel that you’ve entered into the middle of an ongoing conversation. For such reasons I feel that I learned as much about how to be a composer in the dissection of literature as I did in the dissection of music.”

The success of Muhly’s work has increasingly necessitated travel, and his working habits have been adapted accordingly. “Still, essentially,” he says, “my composition process begins with non-musical sketches, lines and texts, basically a map of how the piece will work, an overview on paper. Then there’s a lot of material planning. Half-sketches get tacked up on the wall of whatever space I’m inhabiting. Then I sit with a big piece of manuscript paper and write the music out in my crazy shorthand, which only I can read. That’s the hardest part, the part that requires complete silence. Everything else I can do in a Starbucks. Then, in the process of putting it into the computer, more detail is added, more nuance and structure. I get two drafts printed out, flip through and make changes in red pencil and that’s then sent to the copyist.”

“When I’m setting a text, I print it out in my own format and decorate the page with all the things I’m going to do to it. Then I do those things. With good text I feel I should know exactly what to do. Sometimes a libretto is ninety-five per cent clear and there’s another five per cent where you don’t know how to set it. That’s when you wrangle with the librettist. Two Boys is a police procedural story and the denouement comes down to grammar—the detective is looking at transcripts and notices similar misspellings in all of them and she realizes that they’re all written by the same person. It’s hard to get that procedural texture to come across.”

In the writing of Two Boys Muhly expanded Craig Lucas’s thirty-page libretto to 200 pages. It’s the story of a stabbing of one teenage boy by another, and of the criminal investigation that follows. As the action unfolds it is revealed that the apparent victim has actually determined his own fate, duping his attacker by assuming a series of false identities on the Internet. The boy soprano poses through a chat-room as his schoolgirl sister, an online predator, and an older woman involved in the shadowy world of espionage. These figures appear onstage, along with the deceived teenager, police investigators, and various family members. Muhly’s assured writing for the Two Boys chorus conveys a vivid sense of voices interacting in an online community, sometimes singing from steel towers shrouded in painted gauze and flickering with video projections, sometimes moving slowly across a dimly lit stage, faces illuminated by the open laptops they are carrying.

On the surface, Two Boys presents a distinctively contemporary crime, based loosely on actual events; at the same time it hinges upon a kind of masquerade and sly deception that seasoned opera lovers know well from Cosi fan tutte, Rigoletto, Arabella, and countless other plots. Bartlett Sher’s direction at English National Opera, with those video projections and animations brilliantly—sometimes luridly—realized by 59 Productions, re-created on stage the computer user’s experience of scrolling, following links using rapid transitions. Yet all the while, within this potentially bewildering flow of simulation, the solo voices were collectively telling a solid story, and in two acts within the span of two hours—in recognition, surely, of current attention thresholds—it reached its clear-cut resolution.

“Craig and I conceived Two Boys as having very short arias,” Muhly observes. “We wanted the whole thing to be constantly in motion and wanted to avoid the structural plateaux of lengthy arias.” His second opera, Dark Sisters, a chamber work with libretto by young American playwright Stephen Karam is, on the other hand, aria-based. Scheduled for its first performance at New York’s Gotham Chamber Opera in October, before moving to Philadelphia, it’s the story of a man and his five wives, living in a polygamous community in the desert of America’s southwest. They have numerous children, but the police have taken them all away. “Curtain up is just after the police have left and the women have to figure out what they are going to do,” Muhly explains. “The whole opera is one sleepless night. One woman decides she needs to get out. We hear the story of how she married when she was fifteen-years old, and gradually we learn more about the other wives. So there’s a long aria for one of the sopranos, and each of the others gets her moment.”

The task is to convey a specific sense of Utah and of the conduct of life amongst the Latter-day Saints, while also handling more general issues of collective anxiety and emotional conflict in troubled times. Muhly describes the resultant score as pointillistic, with a touch of Americana. He and Karam have read extensively in the literature of such communities—the so-called misery memoirs; the narratives of women who escaped and felt compelled to tell their tale, sometimes drifting into apparent fantasy; and narratives of compassionate attempts by Mormon society to restore lapsed believers to the fold. Dark Sisters aims to be non-judgmental, while mining this rich source of sociological and psychological material. “It all comes to bear on the fundamental right to choose how you live,” Muhly observes, “but in this case the State takes the kids away. What is never made quite clear in the opera is why the governmental intervention occurred. The actual answer is that somebody called the police and reported that some of those children were being abused. The police couldn’t figure out which were involved, so they took them all. That’s the kind of issue that is hard to make obvious in a libretto, and the kind of thing that never jumps off the page in terms of set-ability.”

For Muhly, such practical problem-solving is clearly another source of pleasure, not least because it involves the sociability of collaborative effort, a lively exchange of ideas and pooling of skills. Music for him is not a matter of mystique, but a process of drawing ingredients together and finding ways to blend them without losing their individual distinctness; balancing craft with ingenuity; getting it done and getting it right. William James famously advised Gertrude Stein, “If you reject anything, that is the beginning of the end as an intellectual.” That might well be Nico Muhly’s tenet as an artist.

In conversation he is alertly receptive, an acute reader of the situation, not fooled by fashion, not swayed by orthodoxy, yet not ruling out any option that might one day meet a creative need or answer to a change in taste. Not phased by the prospect of information overload, Muhly simply aims to sustain the kind of responsiveness that gets results. “In school,” he says, “I had no ambition about what I was trying to do. It was never a case of first I shall acquire this skill and then that skill. I’ve had this whirlwind of a life, but no plan. And it continues to be a very unplanned existence. Who knows, in ten years time maybe all I’m going to want to do is make a five-hour-long anti-narrative thing!”

Audio: Motion (2010). Composed by Nico Muhly. Performed by Aurora Orchestra: Thomas Gould, leader; Nicholas Colon, conductor; Timothy Orpen, clarinet/bass clarinet; John Reid, piano/celesta; Thomas Gould and Jamie Campbell, violin; Max Baillie, viola; Oliver Coates, cello. Image: Sketch working out structural ideas for one of Muhly's orchestral works. Image by: Nico Muhly.