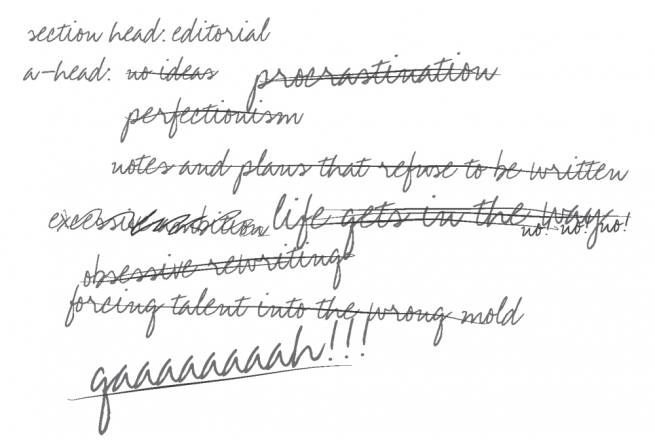

Writer’s block. Google it: 14,100,000 results; it’s popular. Not a problem solely for writers, it could aptly be named creator’s block. Anyone trying to render an idea out of nothingness knows writer’s block’s terrifying implications—missed deadlines, lost revenue, diminished professional reputation. But writer’s block implies more than just threatened livelihood. Ask the creators. The stalling of creativity and the subsequent quiet, creeping catatonia, slowly immobilizes our very identities as artists. In our noncreative stupor our egos ask, what is an artist without art?

Before we identify ourselves as artists, many of us think of being an artist in terms of the artistic product—performers playing, composers having work performed, sound artists exhibiting, and electroacousticians diffusing—rather than in terms of the creative process. When we are told that being an artist is difficult, we assume that the word difficult refers to low living standards and being misunderstood. It is through the experience of creating that we come to understand that difficult can mean painful. As the ideas we conceive refuse to be born, the ways in which we doubt our roles as creative practitioners accumulate.

What do we do with our new identities as noncreators? This issue of Musicworks was curated with this question in mind. Several of the musicians profiled in this issue have experienced some level of writer’s block and they all found different solutions. After years of struggling to express himself, noise artist Brian Ruryk found his voice by working solo. Unsuccessful attempts at collaboration led him to combine his guitar-based performances with the art of Foley. By using found objects to augment his sound palette, he found his sound and started to thrive creatively. Composer Hildegard Westerkamp’s output slowed to a trickle when life got in the way. Being active as a grandmother and spending time with her own ailing mother left little time to write, but once Westerkamp started to really listen to her creative voice, she knew that making the time and space to work needed to become a priority once again. After a fifteen-year break from writing, post-punk rock musician Clint Conley (of Mission of Burma fame) started writing again in what he describes as a possession. Was it his drinking problem or his lack of commercial success that brought his writing to a stuttering stop? He can point to no reasons or solutions for his stop-and-start experience.

Whereas some artists accept the ebbs and flows of creativity without analyzing or questioning the reasons for either state, others attack the problem with the same passion they previously used in making art. There is the search for reasons and for solutions. Who should we trust with these questions? Ourselves? Others? Both. Sit still and listen. Our creativity isn’t a personified muse, or a gift from God. It is the expression of our neuroanatomy meeting our cognitive psychology. Creativity starts with us, and it stops with us.

When answers or solutions don’t come by sitting still and listening inwardly, listen to other blocked artists. There are many voices and a multitude of cultural, psychological, and experiential approaches to the problem of writer’s block. Toru Takemitsu’s collection of essays Confronting Silence, while not a treatise on writer’s block, explains the concepts of ma, the no-sound or negative space that precedes and subsumes all music, and sawari, the physicality of sound, and can be applied to creative flow and block. Choreographer Twyla Tharp calls creative flow the creative habit, and she believes that that flow comes from use and practice. Writer Victoria Nelson uses the principles of humanist psychology to ascribe reasons and prescribe solutions to block.

So. Do we cease to be artists when we stop creating? No. We become noncreators—the ma before the swari. And while we are noncreators we sit and we wait—trusting that creativity is always there.

Image by: Jason Paré.