The first time I met guitarist-composer Amy Brandon, we talked about the lineage of a particular sound.

Her 2019 composition Mimic—written while she participated in the Canadian League of Composers’ Pivot mentorship progam (presented in partnership with the Canadian Music Centre and Continuum Contemporary Music)—contains a percussion technique in which a woodblock set on top of a bowed cymbal is manipulated to shift between overtones. The technique is new for Brandon, but the sound, she tells me, can be traced through the history of free improvisation to the woodblock-and-cymbal explorations of American percussionist Gerry Hemingway.

This moment of cross-genre sonic genealogy says a lot about Brandon’s approach to her music. She often combines contemporary composition with other forms of musical invention, drawn from her work with improvisation and electronics. As a listener, her taste is omnivorous; compositionally, her practice is a meeting place for musical scenes.

The next time we spoke, May 2019, Brandon was back home in Truro, Nova Scotia, where she’s been based for the last ten years. She was in the midst of recording a new album of her chamber works, preparing for an upcoming group improvisation with violist Jennifer Thiessen and saxophonist Ida Toninato in Halifax, and planning The 21st Century Guitar, an interdisciplinary conference, for August 2019 at the University of Ottawa. We talked for a second time about sonic lineage—this time, her own—and the myriad different threads that tie her music together.

Amy Brandon grew up on the east coast of Canada, in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. In 2002, she moved to Ottawa to study jazz guitar at Carleton University, where her early guitar teachers were Roddy Ellias and Garry Elliott—players who moved comfortably between jazz and classical worlds, and who inspired her to do the same. “There was something magical about mastering two very different styles of music,” Brandon explains. “I wanted to do my best to attempt that.”

During those years in Ottawa, Brandon immersed herself in other genres—first in classical guitar, studying on her own and writing classical guitar pieces, and then in free improvisation: “As much as I loved jazz, I kept getting pulled in different directions—and it still wasn’t enough.”

It was also through the guitar that, years later, she found an entry point into electroacoustic composition. The pieces on her debut album, Scavenger (2016) blend solo nylon-string guitar with a quiet, electronic murmuring—sometimes delicate, sometimes urgent, like the whimpering of some sort of frail, ancient creature.

“I’d written quite a lot of solo guitar works, and when I went to record them, something was missing,” Brandon says. “So I took recordings of a lot of my live performances, and I sculpted them into the other half of the album—the electronics and fixed-media backdrops that accompany the works. And then it felt complete.”

Brandon may have floated between disparate scenes, but it doesn’t feel that way: hers is a singular musical voice. She speculates that it’s because as a child, her household was more visual than musical. Her grandmother was a sculptor, and her mother a curator. Growing up, she related to music as a kind of moving sculpture built from shifting three-dimensional forms. More than any particular genre, her work has developed from her sense of music as visceral and visual—literally, shapes in the room.

“There’s a certain corporeality to all the music that I’m attracted to,” she says. “It has a very physical quality that fills the room; it’s the only way that I hear it and see it. And so that’s the way I compose, as well. Timbre, rhythm, pitch—it’s all in service of that.”

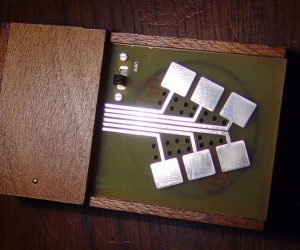

In some of Brandon’s recent work, those physical shapes have made their way into her music in a very immediate way. As part of her current Ph.D. studies in music cognition at Dalhousie University in Halifax, she began researching the visual motor processes involved in guitar performance, and the cognitive connections guitarists make between sound, gesture, and image. While in residence at the Banff Centre for the Arts in February 2017, she began experimenting with virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to put this research into practice. The result was Hidden Motive, a work notated and controlled within an augmented-reality, graphic-score environment. Constructed from three-dimensional, interactive shapes viewed by the musician through a METAVision VR headset, and represented as projections for the audience—the score creates what Brandon calls a secret world, an immersive playing situation, calibrated for the performer alone.

These juxtapositions between real and simulated elements are characteristic of much of her music. In the album notes for Scavenger, jazz guitarist and composer Miles Okazaki refers to Brandon’s works as an “intricate dance of ancient and futuristic sounds.” It’s a striking description, not only because it captures something essential to Brandon’s aesthetic, but because Okazaki could just as easily have been speaking about the shapeshifting nature of the guitar itself—an instrument that, depending on the context, can feel very old or very new.

Brandon embraces it all. “I’m really interested in what’s happening now with the guitar,” she says. “It’s in a strange place right now, where the guitar is becoming less and less a fixture in popular music, having come out of a century where it was basically the instrument of popular music. So what are people doing now to stretch the guitar, to extend the guitar, to use it in different ways that you couldn’t possibly have imagined? And the other thing I find interesting about that is that this kind of stretching and reimagining of the guitar is occurring in all sorts of different genres. Not only with classical players and performers, but also with jazz performers, and with people who work in folk and popular musics as well.

“I’m interested in the cross-pollination that you can end up with,” she adds. “And I’m not interested in purity.”

It’s one of the main reasons behind The 21st Century Guitar, the interdisciplinary conference codirected by Brandon and Montreal-based composer Jason Noble. With concerts, panels, and lectures covering multiple genres and research backgrounds (including guitar pedagogy and cognition), the event is calculated to remedy the siloed nature of a lot of other guitar research, bringing different artists together to talk about how the guitar today, in many fields, is still an unknown element.

When asked about other sources of inspiration, Brandon gives a wide-ranging list: the fluid forms of sculptor Henry Moore, the detail-oriented chamber music of Italian composer Pierluigi Billone, and the writing of Canadian poet David Martin, whose 2014 poem “Tar Swan” appears in the text of her 2017 vocal quartet gouging at a forest sea. The piece opens with urgent muttering, stage whispers that cloud together and shift into the sung, opening lines of Martin’s poem: “As I’ve told you tide and tide again . . . ” About three minutes into the piece, the subtle, underlying electronics creep into the foreground—distortions that add a spaciousness and uncanniness to the text.

The music is a good fit for Martin’s poetry, which is similarly dense and sinuous, thick with often-eerie imagery. It has what Brandon refers to as a multilayered sense of unreality—something she finds herself returning to again and again in her music. “What I’m always trying to capture is this idea of intimate chaos,” she says, “music that both repulses but draws near to you, music that’s pushing you away but also bringing you closer, unreal and anxiety-inducing, but also immediate.”

The closing moments of gouging at a forest sea are like that: layers of text, electronics and sung birdlike gestures that stack on top of one another to form a kind of dark, churning musical current—a tear in the fabric of her intricate sonic world, through which a sense of secret turmoil comes trickling in.

We circle back to talking about sounds and how they come into our lives. Brandon clarifies that her own search for different sounds, and different musics, was rooted in the idea of access—of having a musical vision, and needing every possible genre, and every sonic language she’s ever encountered, to spin it into reality.

“I was and am very greedy,” Brandon says. “I didn’t want to give up any of them.”

And so she hasn’t.

Audio: Artificial Light (2016). Composed and performed by Amy Brandon (guitar, fixed electronics). From the album Scavenger.

Top photo by Jeff Cooke; bottom photo courtesy of the Banff Centre for Arts & Creativity.