“Working with John Chowning at MusicAcoustica in Beijing was like touching history,” confesses a reverent Ian Battenfield Headley during our Skype call. “I had this image of him being this serious composer who doesn't take time to speak to underlings, but he’s actually incredibly nice. The thing is, he has tinnitus, so he doesn't know exactly what his work is sounding like. A big part of my job was to act as his ears during that time. I found a few glaring mistakes with the set-up provided for him, like, they were using Genelec speakers and bass was coming through all eight systems, so I turned them down, or else it would have created some terrible distortion.”

Audio engineer by day, electroacoustic artist by night, Battenfield Headley found his first love, guitar, in the eighth grade, discovering himself a musician with a deep need to compose. “I started to write my own songs and that spiralled out to electroacoustic music by my senior year of high school. At that point, I decided I should get a real theory-and-history background in music while continuing my self-taught music-production skills.”

Battenfield Headley was born and raised in lower Manhattan, the son of visual artists, who used to joke, “Has Ian not learned anything from our lives? Why doesn’t he go study business or accounting?” Towards the end of high school, he veered away from his love of Aphex Twin and Autechre, and delved further into traditionally composed music. Charles Ives, recordings of whose symphonies he inherited on vinyl from his father, struck a deep chord with him, particularly Ives’ seminal piece, Central Park In the Dark.

“Growing up in Manhattan, I knew what it’s like to walk through Central Park at night. The song plays with the city sounds and the solitude of the park colliding [with each other]. It’s a pretty weird piece, at the end of the day; but it really shaped me. I like [the fact] that half of the experience is listening to his work and the inner dialogue it creates when you shut your eyes. That's where my acousmatic fascination comes from. It’s all about that experience.”

Battenfield Headley sees music as a high-level language that can communicate complex emotions, and he intuits that the listener hears tones and interprets them within the fabric of his or her own life. “But acousmatic music is not a romantic ballad. Rather, by using unusual sounds, you put people into an environment that allows them to create an abstract narrative in their minds. With my contest entry Passage I was trying to lead people through these different surreal scenes and abstract ideas. I’m happy with whatever images the audience comes up with—as long as they are feeling something.”

And sometimes, as someone like John Chowning—who discovered FM synthesis almost by chance—knows, the best creations are accidental. An unexpected delay glitch in his Musicworks-award-winning piece Passage just happened to rhythmically mimic the opening bars of Daft Punk’s Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger. “I was worried people might get a dance vibe from that section because they have such a similar rhythm,” muses the composer, slightly self-conscious. “The piece also has some of the typical acousmatic crescendos but I was most impressed by the end section, with the heavy textural sounds that I created by putting a plastic bag over the microphone and crunching it with my hand. I applied a harmonizer to give it a resonant sound, but it’s at least a minute of straight recording,” he says, the audio engineer in him speaking proudly.

“I called it Passage because I tried to let each section be itself and unfold, conclude, and lead into its own section in its own way. That gave me the idea of passing through a tunnel or some sort of musical soundscape where things were not developing, but leading to the next section.”

Battenfield Headley was first exposed to acousmatic music during his studies in sound design, as part of his degree at Northeastern University, where he was immersed in the works of composers like Denis Smalley. “I love playing around with effects for hours and [discovering] all the ways I can make my guitar sound. For example: what would happen if I reversed my guitar track and played it forwards? Acousmatic is the place to do that.” Battenfield Headley also strives to write music that engages the audience, music deviating from the accepted contemporary norms. “I recently started playing with electric guitar by tuning the E string down to a slack low G to inject a sense of unexpected humour into the piece. I want to move away from the accepted musical forms, where every part can be explained—say, from a tone derived from someone’s name. That's a very German way of looking at music. It’s not like I intentionally used a plastic bag in Passage to make a statement on recycling. I did it because, sonically, it sounded good.”

The budding musician is currently sound engineer in residence for the Nonce ensemble of the New England Conservatory. He is working on various improvised electroacoustic collaborative pieces involving spoken word, percussion, and foley artistry.

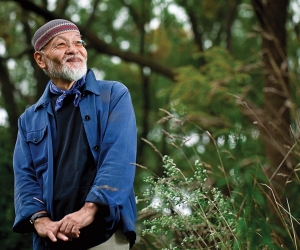

Photo: Ian Battenfield Headley. Photo courtesy of: Ian Battenfield Headley.